In 1936, Great Britain shocked the hockey world by taking gold at the Winter Olympics. Many myths surround this team; this Winter Olympics Special looks at the true story of how Great Britain “stole gold” from Canada.

Whilst the 1936 Summer Olympic Games are perhaps one of the most heavily discussed Games of all time, the 1936 Winter Olympics were also held under the same circumstances in Nazi Germany. Held five months before their more infamous counterparts, antisemitic imagery was removed from the the Bavarian ski-town where the event was held, troops were removed from the vicinity, and two Jewish athletes were allowed to compete for Germany. It was publicly known at the time that the lull in persecution of those deemed Untermensch1 was purely driven by ‘the desire not to offend foreign opinion needlessly.’2. Whilst Nazi iconography was embraced, as many athletes performed a one-armed salute3 towards the German people and the Führer during the opening ceremony4, the most controversial and memorable incident for many was the fact that Canada was beaten in their own game, ice hockey, by Great Britain, losing out on an expected gold medal.

The origins of ice hockey, or just “hockey” for those in the know, are not too dissimilar to those of rugby. Like rugby, hockey as we know it was organised in the nineteenth century; however, similar games have been played for centuries across the globe5. Ice hockey, as we know it today, was primarily developed in Nova Scotia. Colonists from Europe brought games such as bandy, shinty, and hurling with them and adapted them to the local climate and conditions. Local indigenous peoples also had stick and ball games played on ice, and sticks from the Mi’kmaq tribe were soon in vogue with the white colonists. Unsurprisingly, a company owned by white colonists, the Starr Manufacturing Company of Dartmouth, began producing ‘Mic-Mac’ sticks6 which were an instant hit.

Men in Great Britain began playing organised ice hockey in the 1890s, roughly two decades after the first organised, indoor hockey game was played in Montreal in 18757. The exact date of the first organised ice hockey game in Great Britain is debatable, as bandy had popular across East Anglia for a long time. We do know, however, that organised domestic competition was taking place as early as 1898, with the Admiral Maxse Challenge Cup being awarded to the English club champions8. Interestingly, many of the early club champions had Canadian-themed names such as the Niagara IHC and the London Canadians.

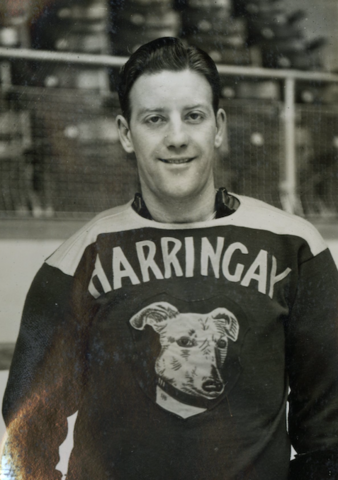

The interwar period was a golden age for British Ice Hockey. After the British Ice Hockey Association was reformed in 1923, having been a founding member of the International Ice Hockey Federation in 1908, the national team won bronze at the 1924 Olympics9 . From there, the popularity of the sport, especially in London, was explosive. The domestic game was an extremely popular spectator sport, the magazine Ice Hockey World being read by 50,000 people per week. Hockey had previously been confined to the Manchester Ice Palace, but following the explosion, rinks began popping up all over the country. The Grosvenor House Hotel in London uniquely had an ice rink up until 193510, and was home to the Grosvenor Canadians. The Canadians would go on to move to Wembley in 1934, where they frequently brought in crowds of 10,000, and were eventually renamed the Wembley Monarchs.

The domestic game had taken off to a degree that allowed clubs to recruit overseas players, primarily Canadians, to play in Britain. Whilst the game in North America was primarily professional, the game in Britain was amateur in theory. Players were paid upwards of £10 per week, but they were nominally employed by local businesses or by the rinks themselves. The faux-amateur status of the British league allowed for the best British players to play in international competitions, which followed the Olympic amateur rules. In contrast, the best players in North America were professional, with the majority playing in the National Hockey League, and were therefore banned from Olympic competition. Canada, therefore, opted to send established senior amateur sides to international competition under the Canadian banner.

The initial domestic boom had been caused by international success. However, despite the boom, the British national side continued to finish third and fourth in various international competitions after 1924. After another third-place finish at the 1935 World Championships, the BIHA were frustrated. Whilst the domestic game had improved, the nation’s international standing had not changed.

Bunny Ahearne11 had been born in Ireland in 1900 and had never played ice hockey, yet he would become one of the most important figures in British ice hockey history. A travel agent by day, Ahearne was both the secretary of the BIHA and the head coach for the national team during the 1935 World Championships12. Aware of the Olympics the following year, Ahearne decided to take action. Ahearne decided to recruit Richmond Hawks head coach Percy Nicklin to be the new head coach of the national side. Nicklin was Canadian with Scottish parents and was among the most experienced coaches in Britain at the time. Having won the Allan Cup13 twice with New Brunswick’s Moncton Hawks in 1933 and 1934, Nicklin moved to England to coach the Richmond Hawks14.

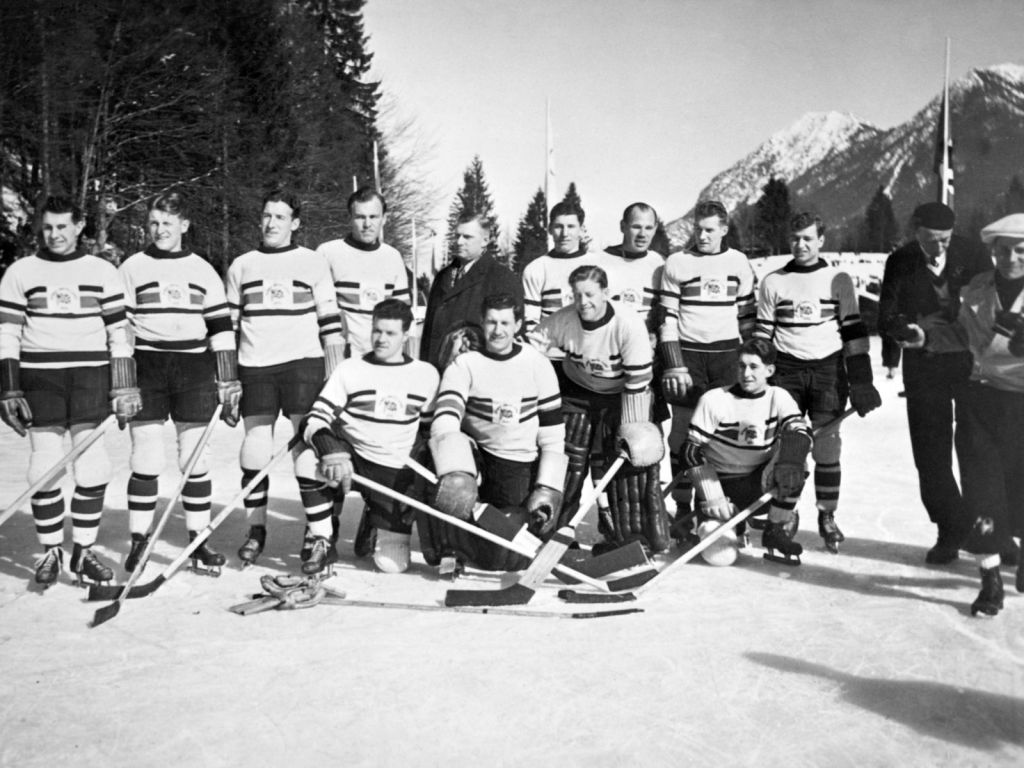

With a new Canadian coach in place, Ahearne was ready to build his squad. Previous British representational sides had been made up of army officers and professionals who had primarily been born and raised in Britain15. However, Ahearne had a different idea. Inspired by the influx of Canadian-trained and/or born players playing in the British leagues, Ahearne decided that creating a squad based on Canadian-trained players would be key to success. Ahearne travelled to Canada in the summer of 1935 to trawl for British-born players and brought with him captain Carl Erhardt. Erhardt was an extremely experienced player, and at 39 was expected to be one of the oldest, if not the oldest, hockey players at the Olympics. Born in Britain to German parents, Erdhardt had been educated in Germany and Switzerland, where he learnt the game16.

Migration from Britain to Canada was exceptionally common, and nationality law was extremely different from today. As a member of the British Empire, Canadians were considered British Subjects and Canada itself would not have a distinct citizenship law until a decade later in 1946. As such, it was not difficult for Ahearne to find players who had been born in Britain; what proved tricky was convincing the Canadian authorities to let the players leave. With great difficulty, Ahearne reached an agreement with the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association that the BIHA would only sign players who had been approved to move by the Canadians. In total, eight British-born, Canadian-raised players would sign for British teams and go on to represent the nation of their birth through this arrangement17. This group of eight, including Nicklin’s two-time Allan Cup-winning goaltender James Foster, joined Erhardt along with Robert Wyman, the only member of the squad to be born and raised in Britain, and Gerry Davey and Gordon Dailley, who had both been born in Canada and moved to London during the Great Depression, in the British squad.

Preparation for the tournament had gone well, thanks to what was considered an advanced training regime and structured defensive play courtesy of Nicklin18. The team were hopeful upon their arrival in Bavaria, but they soon found themselves in hot water. The Canadians claimed that goaltender James Foster, who had been born in Scotland and moved to Manitoba aged 7, and winger Alexander Archer, who had been born in England to Scottish parents and moved to Manitoba aged 3, had not received permission from the CAHA to move. Whilst it was erroneously suggested back in Britain that the pair had been banned from hockey due to their conduct in Canada19, the pair were accused of simply not adhering to the agreement made between the British and Canadian governing bodies the previous summer. The International Ice Hockey Federation voted unanimously to ban the pair, however two days after the vote, both players took the ice. David Wallenchinsky notes in his 1984 book on the Olympics that there are various schools of thought regarding this. Whilst the British claimed that the Canadians relented and allowed the pair to compete as a sign of good faith and ‘pride in their Commonwealth status‘, the North Americans claimed that the Brits simply ignored the ban20. British newspapers from the period claim that the ban was lifted against the Canadians’ wishes by the IIHF before the games began2122. The president of the CAHA, one E. A. Gilroy, stated that not only were the pair still under a ban, but that upwards of thirty other Canadian ‘pucksters’ playing on English teams were also banned from playing ice hockey23.

With the British team thinking that they had put the drama behind them, they moved into the first stage of the competition. The fifteen teams enrolled in the event were split into four pools. Whilst three of the pools featured four teams, Great Britain found themselves the top seed in their pool of three. Britain found itself sailing past both Sweden and Japan, with James Foster recording a shutout24 in both games. Interestingly, Japan’s goalie Teiji Honma became the first ice hockey player to wear a mask at the Olympics in his game against Great Britain25.

The top two from each group in the first stage of the competition qualified for a second round robin. This time, Great Britain found themselves in a pool of four against four-time Olympic Champions Canada, home nation Germany and Hungary. Canada and Great Britain faced off on the 11th February 1936, in what would become the defining game of the tournament. The German crowd was reportedly, and somewhat surprisingly, supporting the British, as the Canadians were accused of ‘whinging’26. Whilst the rest of the second stage of the competition would go on to be dominated by the Canadians, with a 15-0 win over Hungary and a 6-2 win over Germany, they fell 2-1 to Great Britain thanks to a late, last-period screamer by Ontario-raised winger Edgar Brenchley27. Britain would go on to draw against Germany, who did not play German-Jewish player Rudi Ball due to injury, and a 5-1 win over Hungary.

The final round of the Olympics would be extremely controversial and resulted in yet another complaint from the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association. Tournament rules dictated that the final round of competition was yet another round robin, competed by the top four sides of Great Britain, Canada, the USA and Czechoslovakia. However, in order to save time at the 1936 games, relevant results from the second round were carried over into the third round. The Canadians were incensed. Not only was this against convention at the time, but it also put them at a significant disadvantage in the final round. Whilst they attempted, twice, to change the format prior to the third round, their requests were denied. Whilst this had come as a shock to the Canadians, the somewhat bizarre round robin format had been explained prior to the beginning of the games at a delegation meeting. However, both the Americans and the Canadians had decided not to attend the meeting. Due to the strange format, not only did the USA’s 2-0 win over Czechoslovakia count, but so did Great Britain’s 2-1 win over Canada. Whilst Canada managed to beat their neighbours 1-0 and Czechslovakia 7-0, the loss stood firm. Great Britain on the other hand also beat Czechslovakia but fought against the USA for six goalless periods. Whilst modern rules do not allow for an ice hockey game to end in a draw28, this was not the case for 1936. Having played one less game in the first round and recording two draws, Great Britain claimed the gold over Canada by one single point.

‘England won because she was better coached, and you can give all the credit in the world to our coach, Percy Nicklin. England played typical Nicklin hockey, the sort of hockey which he taught the double Allan Cup winners, Moncton Hawks. We went out to get a goal and when we got it we played a tight defensive game.’

-Alexander Archer, 193629

It is fair to say that Canada did not take their silver medal well. With statements not unfamiliar to anyone who has spent any time on rugby Twitter or Reddit, it was claimed by the canucks that the British team was essentially Canadian anyway and that the competition rules had not been explained to them. The second statement is, in fact, true; the rules had not been explained to the Canadians. However, this was only because the Canadians had not attended the meeting in which this was explained. However, stating that the team was essentially Canadian is a little trickier to unpack.

All but two of the thirteen-man squad had a connection to Canada. Nine had emigrated to Canada as children, whilst two more had been born there to British parents. Nationality and citizenship law in 1936 were significantly more lax than in 2026; it would be the following World War which changed this. However, we can see from the outrage of the Canadians even prior to their loss that there was a sense of Canadian Nationality, distinct from that of a British dominion, building. Whilst it may have upset the Canadians, all of the British team qualified for Great Britain via birth or birthright. The continued emphasis on Great Britain’s “Canadianness” can even be seen as recently as 2025, with the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Timeline of the Game stating that the Canadians not only lost on a technicality30, but that the British team was effectively Canadian31.

Author’s note: I hope that you enjoyed this Winter Olympics Special, even if it technically isn’t ‘rugby history’. I personally like to say that hockey and rugby are the same sport, but in different fonts. Whilst Team GB do not have a spot in either the men’s or women’s competition at the 2026 Winter Olympics, if anyone needs me over the coming weeks, I will be sat in front of the television watching every second. The women’s competition starts on Thursday 5th February, and the men’s on Wednesday 11th February.

I also wanted to take a moment to reflect on the disturbing similarities I found between the normalisation of a fascist regime by athletes in 1936 and the current state of the world. At the 1936 Winter Games, athletes from around the world performed Nazi salutes to Adolf Hitler and the German public. Much like Elon Musk in 2025, athletes claimed afterwards that it was an Olympic, or “Roman”, salute. Similarly, the nitpicking over the ethnicity and nationality of the British ice hockey team, along with the pressure on the Nazi’s to include two Jewish athletes in their delegation, brings forth the West’s obsession over immigration in the twenty-first century.

So far in 2026, the world has seen two American citizens shot dead by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, in broad daylight and on camera, after being sent to Minneapolis as a part of Donald Trump’s ‘focus’ on immigration. Whilst the murders of Renée Good and Alex Pretti have quite rightly sparked outrage as well as calls for the abolition of ICE, it should also be at the forefront of our minds that they are not the only victims. 43 year old Keith Porter Jr, a Black American citizen, was shot dead by an ICE officer in Los Angeles on New Years Eve, there has been little reporting on his death and when there has it has come with a heavy dose of the propaganda reserved for Black men. Beyond the shootings of citizens, 2025 was ICE’s deadliest year in two decades, with December 2025 being the worst on record. Thirty-two people died in ICE custody in 2025; this number does not include those who were killed on the streets nor those in Border Patrol custody. With reports that ICE agents will be attempting to attend the 2026 Milan-Cortina Games as a part of American Vice President JD Vance’s entourage32, the attempts to normalise the USA’s fascist regime have gone global. With the USA set to co-host the Men’s FIFA World Cup this summer, as well as other international sporting events such as a stop for the SVNS circuit, and the Summer Olympics in 2028, it is important that not only do athletes and spectators not bend to the normalisation of the regime, but to also ensure the safety of both those visiting the United States and those residing there. Equally, closer to home for myself, we can see how Britain is sliding further to the right with several political parties echoing far-right statements of the American government.

I would like to thank two of my favourite North Americans, Julia and Peach, for proof-reading this article. I appreciate you both very, very much.

If you would like more regular updates, please check out my instagram, twitter and/or bluesky. You can also catch me podding every Tuesday morning with WRRAP. An audio version of this post is also available in all good podcasting locations, and as always, references are below.

-Hattie

Thanks for reading The Rugby History Project! Subscribe for free to receive new posts, or consider upgrading to Historian Tier to support the project!

- Untermensch directly translates to ‘underman’ or ‘subhuman’ in English. It was a term used in Nazi Germany to categorise non-Aryan peoples such as Jews, Roma and Slavic peoples as well as those with mental or physical disabilities, dissidents and queer people. ↩︎

- Belfast Telegraph, “1936. Shot Nazi Leader. Berlin Angry at the Crime. German Press Outcry. Effect of Olympic Games,” Belfast Telegraph, February 6, 1936 <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002318/19360206/142/0008>. ↩︎

- No, Elon its not a “Roman salute”. It’s a Nazi salute. ↩︎

- Adam Martin, “So This Happened: Hitlers Winter Olympics in Photos,” New York, February 12, 2014 <https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2014/02/this-happened-hitlers-winter-olympics.html>. ↩︎

- Don Weekes, Hockey Hall of Fame Timeline of the Game: 150 Years of Hockey Stories, 2025, pp. 11. ↩︎

- Don Weekes, Hockey Hall of Fame Timeline of the Game: 150 Years of Hockey Stories, 2025, pp. 12. ↩︎

- Don Weekes, Hockey Hall of Fame Timeline of the Game: 150 Years of Hockey Stories, 2025, pp. 17. ↩︎

- Michael A Chambers, UK Ice Hockey (Amazon, 2018), 20. ↩︎

- “The Forgotten Story of Great Britain’s Gold at the 1936 Winter Games,” TNT Sports, February 2, 2018 <https://www.tntsports.co.uk/ice-hockey/fascism-and-gb-s-ice-hockey-gold-in-1936_sto6499246/story.shtml>. ↩︎

- It was taken down and replaced with a grand ballroom. Booooooo. ↩︎

- John Francis was his actual name; I have yet to find an explanation for the nickname ‘Bunny’. ↩︎

- “HHOF | Honoured Members | Player | Bunny Ahearne,” Hockey Hall of Fame <https://www.hhof.com/HonouredMembers/MemberDetails.html?type=Player&mem=b197701&list=ByName>. ↩︎

- The Allan Cup is the trophy for the amateur senior hockey champions of Canada. ↩︎

- “The Forgotten Story of Great Britain’s Gold at the 1936 Winter Games.” ↩︎

- “The Forgotten Story of Great Britain’s Gold at the 1936 Winter Games.” ↩︎

- BBC Sport, “BBC SPORT | Winter Olympics 2002 | Ice Hockey | British Skate to Victory,” BBC Sport, January 29, 2002 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/winterolympics2002/hi/english/ice_hockey/newsid_1647000/1647885.stm>. ↩︎

- “The Forgotten Story of Great Britain’s Gold at the 1936 Winter Games.” ↩︎

- Ice Hockey UK, “Percy Nicklin – ICE Hockey UK,” Ice Hockey UK, July 11, 2024 <https://icehockeyuk.co.uk/hall-of-fames/percy-nicklin/>. ↩︎

- Leicester Evening Mail, “Winter Olympic Games Sensation: Britain’s Ice Hockey Withdrawal?,” Leicester Evening Mail <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0003330/19360206/221/0013>. ↩︎

- David Wallechinsky, The Complete Book of the Olympics (Penguin Books, 1984), pp. 608-609. ↩︎

- Daily Express, “Winter Olympics – Ban on British Players Lifted,” Daily Express, February 11, 1936 <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0004848/19360211/340/0014>. ↩︎

- Western Daily Press, “Olympic Games Ice Hockey,” Western Daily Press, February 10, 1936 <https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000513/19360210/015/0003>. ↩︎

- Winnipeg Tribune, “Gilroy Denies Bans against Archer and Foster Are Lifted,” Winnipeg Tribune, 1936 <https://newspaperarchive.com/sports-clipping-feb-08-1936-1709414/>. ↩︎

- He did not concede a single goal in the first stage. ↩︎

- “Legends of Hockey – Gallery – Masks, 005” https://web.archive.org/web/20110525203259/http://www.hhof.com/LegendsOfHockey/htmlgallery/gallery_masks005.shtml#x. ↩︎

- “The Forgotten Story of Great Britain’s Gold at the 1936 Winter Games.” ↩︎

- Wallechinsky, The Complete Book of the Olympics, pp. 609. ↩︎

- Various combinations of overtime and penalty shootouts are used. ↩︎

- Puckstruck, “Winterspiele 1936: The Revenge of Jimmy Foster,” Puckstruck, January 4, 2022 <https://puckstruck.com/tag/percy-nicklin/>. ↩︎

- The technicality being that they lost. ↩︎

- Weekes, Hockey Hall of Fame Timeline of the Game: 150 Years of Hockey Stories, pp. 74. ↩︎

- Al Jazeera, “Milan Protests Decry ‘Creeping Fascism’ of ICE Role at Winter Olympics,” Al Jazeera, February 1, 2026 <https://www.aljazeera.com/sports/2026/1/31/milan-demonstrators-decry-creeping-fascism-of-ice-role-at-winter-olympics>. ↩︎

Leave a comment