In many countries, rugby union is considered to be a sport for the middle classes. Stereotypically played in private schools by the sons of professionals, the sport often struggles to overcome this perception. However, how true is this reputation and why did the sport gain it in the first place?

Whilst full contact footballing codes have existed across the globe for centuries, the code of rugby union has direct links to a small English public school. Whilst the sibling code of rugby league has the reputation as the ‘working mans sport’, rugby union is considered by many to be ‘posh’ and a sport for the middle classes. Whilst the definition of middle class has evolved since the Victorian era1, the over representation of privately educated players in many national men’s squads is equally as true in 2025 as it was in 1895. In the 2025 England Men’s Six Nations squad, 20 players (57%) had attended fee-paying schools2. In contrast, 6.4% of school children in Britain attended a fee-paying school in the 2024/25 school year3. The legacy and networks of private schools and prestigious universities are interwoven with rugby union history across the globe and contribute to the stereotype of the ‘posh-ness’ of rugby union. But why exactly is rugby union so tightly woven with private education and the middle class?

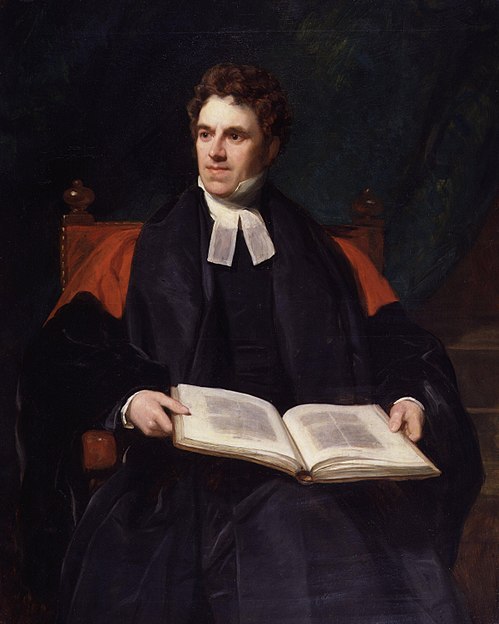

To understand why rugby union is seen as posh, we must first understand the origins of the sport itself as well as the socio-economic conditions of the period in which it was created. Rugby rules football originates at Rugby School, a public school4 in Warwickshire, England. Whilst an education at Rugby School was not attainable for most of those living in Britain during the nineteenth century, it was not considered an elite public school like Harrow or Eton5. Rather than being attended by the aristocracy and extremely wealthy, Rugby schoolboys were the sons of the clergy, rural gentry and upper middle class businessmen6. The school underwent reforms under headmaster Thomas Arnold from 1828 to 1841, with a focus on masculine Christianity and would later become the blueprint for Victorian public schools7.

Like most public schools, Rugby School developed their own football rules. However, unlike most schools, rugby rules spread beyond the school as a codified game. The successful spread of rugby rules comes down to three major factors. Firstly, Old Rugbeians8 set up rugby rules football clubs9 and were not shy in professing the superiority of rugby rules football. Secondly, the game had been immortalised in Thomas Hughes’s 1857 novel Tom Brown’s School Days. The novel was reportedly written as a guide to Rugby School for Hughes’s son and is based on the experiences of Hughes and his brother George who had attended the school during Arnold’s tenure. Famously, the book describes a game of rugby rules, and introduced the game to the wider public. As an extension of Arnold’s philosophy and Rugby Schools reputation, historian Tony Collins notes that rugby football itself became an ideology10. Thirdly, perhaps most importantly, the game was a more organised version of the full contact football codes which had been played for centuries.

With a strong group of rugby rules football clubs, including the likes of Blackheath and Richmond, when the Football Association codified their rules and excluded the practice of hacking, rugby rules football clubs were able to eschew membership and continue to operate independently. Rugby and athletics clubs became a way for middle class men to not only exercise, which was a fundamental element of muscular Christianity, but also to network and socialise with other like-minded and well connected men. These clubs were more than a local phenomenon as the game had spread across England, with a stronghold in the North, and clubs and school teams in Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

The 1870s saw the first international representative test matches and the formation of the Rugby Football Union. The formation of a governing body and creation of the rugby law book in 1871 soldified the class structures within rugby which had already begun to form. The delegetion which formed the RFU in 1871 was made up of representatives from twenty-one clubs11. However, all of the clubs represented were London based, all of the representatives were upper-middle class professionals and the majority were Old Rugbeians. The three members chosen to write the law book were also Old Rugbeians12, meaning that play variations created by non-Rugbeians were not considered. The domination of Old Rugbeians continued, with the first five RFU presidents also being from the school13. Old Rugbeians were also responsible for the biggest myth within rugby history, a creation which aimed to legitimise class hierarchy within the sport.

The myth of William Webb Ellis has endured through to the 21st century, with the name featuring on the Men’s Rugby World Cup trophy. The myth of the school boy who picked up the ball and ran with it has been used in official RFU advertisements too. The story is perfectly poetic and seems almost too good to be true. And that would be because it is. There is simply no evidence to suggest that William Webb Ellis even played football14, let alone revolutionised the game. The story probably originates with Matthew Bloxham, a former local pupil of the school who went on to write for school magazines. One of these stories, dating to 1876, involves William Webb Ellis and his supposed invention15. The story was written at point in time in which Old Rugbeians, and the upper middle class generally, were beginning to feel their grip on the sport slip. Over half of the rugby clubs in England were based in the North, where the game was played by predominantly working class men. Rugby was simply a codified version of similar local games rather than an example of the display of the Christian masculinity of the elite. As a way to “correct” this view, the origin myth of William Webb Ellis allowed the Old Rugbeians to hold on to the supposed ownership of the game.

Despite, or rather in spite of, the ownership myth, rugby in working class communities in the North of England continued to grow. The 1886 ban on professionalism, which ostensibly banned all forms of payment to players, not only disproportionally affected working class players but also was enacted to weaken the burgeoning power of Northern clubs16. In the late eighteenth century, over half of the member clubs of the RFU were based in Yorkshire and Lancashire. In terms of individuals, Yorkshire and Lancashire players made up 48% of the adult memberships of the RFU17. Northern teams were also extremely successful by all metrics. Not only did the teams bring in results on the pitch, resulting in a large proportion of Northern, working class players being selected for international duty, but the games were well attended which resulted in healthy coffers for clubs in economically disadvantaged areas.

Rugby had not been designed to be a spectator sport and the RFU rallied against the idea of marketing it as such. Early attendance figures were simply not recorded as attracting spectators was simply not a goal of the game. The culture of Northern rugby was distinctly different to its southern rulers, with intense rivalries based on geographic location, rather than school or university affiliation, which spread beyond the players themselves. Whilst post-match networking was professionally advantageous for middle class players, post-match celebrations in the North simply did not benefit working class players to the same degree. The benefit of middle class rugby in London was the social connections and the display of Christian masculinity, the benefits of working class rugby in Lancashire and Yorkshire were putting on an event that could be attended by all, with economic benefits for the clubs themselves. The culture of Northern rugby was seen as lesser-than by those from London, with the lack of public school influence seen as a terrible affront to the sport.

‘The majority of Yorkshire fifteens are composed of working men who have only adopted football in recent years, and have recieved no school education in the art.’

-London Commentator, 189218

As the success of Northern clubs grew, as did their desire to be accurately represented on the RFU board and for their concerns to be heard. London based clubs were over represented on the RFU board and beyond that, committee meetings were only held in London which often excluded the few Northern representatives. Whilst the North had supported amateurism within rugby, they believed that broken time payments did not constitute as professionalism. Broken time simply referred to the practice of paying players for wages lost from their day jobs due to rugby commitments. Whilst middle class professionals were either not affected by loss of earnings or did not experience it all, working class players were severely impacted by their loss of earnings. With little representation, Northern clubs were unable to advocate successfully for broken time payments and between 1886 and 1895, many were hit with professionalism charges. Amateurism was not a founding principle of rugby, but rather a weapon added to the sport to disadvantage working class and lower middle class players. Whilst the events of 1886 may have come out in favour of the RFU board if they had occurred a century previously, the Labour movement had empowered the working class. As a direct consequence of the RFU’s preferential treatment of London based teams and the disenfranchisement of working class players, the Northern Union, and the sport of rugby league, was born.

‘[if the working class player] cannot play the game for the game itself, he can have no true interest in it, and it were better that he left us.’

-Frank Mitchell19

The links between the middle class and rugby don’t just exist in England. The spread of rugby has historically been intertwined with colonialism and the British Empire. Whilst the RFU itself was not directly involved in the spread of the game, and also technically was not in charge of governance of the game following their addition to the IRFB in 1890, their influence was seismic as de facto rulers of the rugby world. The network of old public school boys and officers in the British Army led to a global expansion of the game. Whilst some nations have been able to move away from the same connotations that the game has in England, the foundations are identical.

As to be expected, the first countries that rugby expanded to were Wales, Scotland and Ireland with instances of rugby rules being played in Wales in 1850 and in 1854 in both Ireland and Scotland. In each instance, the game was brought to the nation by former public school boys from England. Rugby in Scotland initially mirrored the game in England. Primarily played at newer public schools, attended by the sons of upper middle class business men, clergy and professionals. The games hub was in the capital city, but the Border region also had a significant rugby playing population. Unlike the game in Edinburgh, rugby in the Borders had less of a class based structure and developed as a codified alternative to the local game of Ba’20. The Borders based players faced challenges when it came to facing international selection. Whilst many of Scotland’s greatest ever players have come from the Borders, including the likes of current Scotland Men’s coach Gregor Townsend21, Borders players often had to work harder to be recognised by international selectors. Due to the intense networking of the middle classes in Edinburgh, provincial players who had not attended public school struggled in comparison.

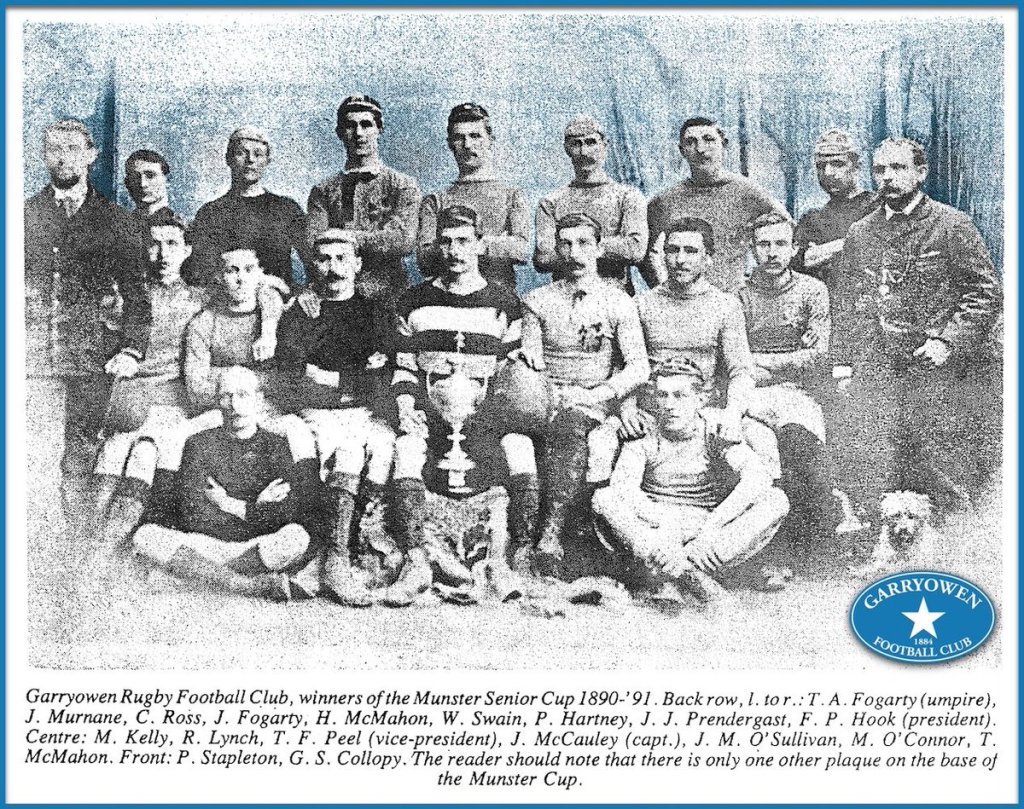

Trinity College Dublin’s rugby club DUFC was founded in 1854. Meaning that rugby predated Catholic admission to the university by nineteen years22. Despite their exclusion from the original rugby club in Ireland, upwardly mobile Dublin Catholics took on the game within the private school system following an 1868 publication of the rules in a cricket annum23. Rugby became incredibly important to the Dublin, and to an extent wider Leinster, middle class Catholic culture. Unlike the unorganised structure of English rugby; cups and leagues were a key element of Irish rugby from the start. Dublin private schools, such as Blackrock College, have built their reputation on their success in rugby competitions and their pipeline to the national team. In the North, rugby had strong connections to the Protestant Unionist community, but the economic demographics stayed the same, as the game stayed the prerogative of the middle classes24. Generally speaking, rugby developed as a game for the privileged elite, both Catholic and Protestant, in Ireland. The exception to this is in Munster, where class was not a barrier to involvement due to open clubs and a desire to be competitive. Unlike Dublin, in which rugby was played equally across the middle classes regardless of religious denomination, Munster was predominantly Catholic. Unlike Protestant sensibilities which forbade sport on Sundays, Catholic culture saw no issue with rugby on the Sabbath. The extended playing window on weekends allowed working men to participate25. Whilst clubs may have initially been drawn across class lines, clubs like Garryowen showed that talent did not have a class distinction, with the club winning all but two Munster Senior Cups between 1889 and 190026.

Many rugby fans will tell you that rugby isn’t just a sport for posh public schoolboys, because the game in Wales is for everyone. Unfortunately this isn’t quite true. Whilst Welsh Men’s national team selections have historically featured significantly less privately educated players than any of their closest rivals, class has always played a part in rugby in Wales. Rugby rules football was introduced to Wales through St. David’s College27 and Llandovery College2829, before spreading to the few fee paying education institutions and grammar schools in Wales. Rugby spread through all sections of society in a way which had not been seen in other countries. However, despite the wide playing pool and love for the sport in Wales, class did hamper the careers of many. Grammar school educated players, who went on to university, were able to play without the concerns of making a living for a longer period of time than those who left school and went into manual labour. Whilst a blind eye was turned to the practice of ‘boot money’ in Wales30, many players felt intense economic pressure. To counter this, thousands of Welsh players, including British and Irish Lions and national team captains, turned to rugby league and went North. “Going North”, especially during periods of economic trouble, directly affected the international success of the Welsh national team. The phenomenon disproportionally affected Wales in comparison to their Irish and Scottish counterparts, and within Wales affected working class players more than their middle class counterparts. Those from immigrant and/or minority backgrounds were disproportionally more likely to Go North, partially for economic reasons and partially due to racism and xenophobia within Welsh rugby.

‘Imperialism doesn’t only arrive with bombs and bases; it also arrives with jerseys’

-Social Rights Ireland, 202531

The spread of rugby beyond the Home Nations can easily be linked to British Imperialism during the late nineteenth century. In France and Italy the sport was introduced by British businessmen who had played the sport at their English public schools32. Similarly, the game was introduced to Argentina through the surprisingly large, and wealthy, British population33. The game thrived in Argentina, as much like their English counterparts, the code was used as a way to separate the upper middle class elite from their working class compatriots. Aside from these three notable exceptions, the vast majority of ‘traditional rugby nations’ were introduced to the sport through British colonialism.

Whilst the British Army contributed to the spread of rugby in Commonwealth countries such as Canada, Fiji and India; as major outposts in the British Empire, footballing codes in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand developed in a similar manner to Britain. When rugby was introduced to these nations in the latter half of the nineteenth century, it was through traditional channels: in Australia through Sydney University and in Aotearoa through a politicians son, who had been educated in London. In both cases, rugby was seen as a way to connect their nations with what was often described in contemporary sources as the ‘motherland’. Complex colonial attitudes often meant that nations within the British Empire saw themselves as British, and white colonial society dictated that cultural links were upheld. Whilst rugby in New Zealand has a social role similar to the one it has in Wales, rugby union in Australia is heavily linked to the private school system. As a nation with multiple competing football codes, including the native Australian Rules, the code of football in which someone participates in is often seen as a signifier of their class affiliation. Rugby union is heavily linked to the private school system, whilst league is seen as the working mans game.

Unpacking the societal conditions of rugby in South Africa requires both sensitivity and time for which this article does not have the bandwidth for. However, it is undeniable that between the introduction of the game in 1861 and the end of the Second Boer War in 1902 the game was played almost exclusively by affluent British immigrants and British soldiers. It is also of note that whilst in the last few decades, rugby has expanded significantly, there is still a heavy focus on schoolboy rugby for the development of players and that the schools involved are generally either fee paying or elite state schools.

Most discussions of class within rugby omit women’s rugby entirely from their discussions. Whilst much of this is probably rooted in the general apathy from many towards the women’s game, it is also due to the fact that there is a belief of class being less of a factor in the women’s game. Women’s rugby began as a counter culture movement, with women taking on what is seen as a hyper masculine, contact sport during second-wave feminism. However, the women who embarked on this endeavour were predominantly university students3435. Whilst social mobility in the 21st century has allowed for more working class people than ever to achieve tertiary education, during the twentieth century a university education was very much the prerogative of the middle and upper classes. Beyond this, pursuing rugby during this era would’ve come at a financial cost, and time commitments, for the participant which may have been prevented a working class player being able to access the elite level. The Founding Four of the Women’s Rugby World Cup in 1991 were all university educated, middle class professionals living in London, not too dissimilar from the privately educated, upper-middle class professionals who founded the RFU in London in 187136. Class features heavily in Jacob Bassford’s paper on the 1991 Rugby World Cup, in which he mentions an anonymous participant describing the host venues as ‘the middle of nowhere’ and ‘the backwaters of Wales’37, showing that classist attitudes also exist in women’s rugby38.

Whilst it is undeniable that women’s rugby demographics are significantly different to that of the men’s game, the set up of elite women’s rugby is reliant on the same systems which allowed amateurism to uphold the status quo in men’s rugby for over a century. Very few female rugby players attend fee paying schools, even in countries in which the men’s game relies on that system. Even into the current era, women’s rugby is reliant on the university system in many nations. Either through the use of university competitions to develop talent39 or through the exploitation of labour of university students in senior competitions. This system puts the sport out of the reach of many working class women and young girls who are either unable to reach university or are unable to fund the sport at this level.

So in conclusion we return to our original question: why is rugby posh? The answer is pretty simple: it was designed and legislated to be such by the Rugby Football Union.

I hope you have all enjoyed the seventh edition of The Rugby History Project. I must apologise for the gap since my last article, the Rugby World Cup wiped me out mentally and physically! I hope that this discussion has interested you, it really is a topic which could take up a whole book but I tried to keep it as concise as possible. If you would like more regular updates, please check out my instagram, twitter and/or bluesky. An audio version of this post is also available in all good podcasting locations and as always, references are below.

-Hattie

Thanks for reading The Rugby History Project! Subscribe for free to receive new posts, or consider upgrading to Historian Tier to support the project!

- Class definitions are complex and constantly evolving. The middle class in Victorian Britain was significantly more narrow than it is in the 21st century, and definitions are completely different in other cultures. This article does not discuss the complexities of the British class structure but rather uses loose definitions based on fee paying schools and careers. ↩︎

- Jenny Mollon, “Six Nations Rugby 2025: Where Did England’s Top Rugby Players Go to School?,” Which School Advisor, April 8, 2025 <https://whichschooladvisor.com/uk/school-news/six-nations-rugby-2025-where-did-englands-top-rugby-players-go-to-school>. ↩︎

- Kate McGough and Harriet Agerholm, “Over 11,000 Fewer Pupils at Private School This Year,” BBC News, June 5, 2025 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c2lk2p7wpr4o>. ↩︎

- Public school in the UK refers to selective, fee paying schools independant from the local authority. ↩︎

- Huw Richards, A Game for Hooligans, 2nd edn (Mainstream Publishing, 2007), pp. 19. ↩︎

- Tony Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, (Routledge, 2009), pp. 5. ↩︎

- Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, pp. 7-11. ↩︎

- Old Rugbeians refers to previous pupils of Rugby School. ↩︎

- Initially at univerisities and then adult clubs. ↩︎

- Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, pp. 12. ↩︎

- Supposedly it was planned to be 22 but the representative from Wasps went to the wrong pub. ↩︎

- All three were also lawyers, hence why rugby has laws and not rules. ↩︎

- Richards, A Game for Hooligans, pp. 41. ↩︎

- By all accounts he was a great cricketer. ↩︎

- “BLOXAM, Matthew Holbeche,” Rugby Local History Research Group <https://www.rugby-local-history.org/biographies/bloxam-matthew-holbeche/>. ↩︎

- Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, pp. 27. ↩︎

- Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, pp. 27. ↩︎

- Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, pp. 28. ↩︎

- Mitchell in Tony Collins, The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015), pp. 43. ↩︎

- Eleanor Bradley, “The Borders,” Rugby Journal, April 25, 2025 <https://www.therugbyjournal.com/rugby-blog/the-borders>. ↩︎

- Bradley, “The Borders.” ↩︎

- Collins, The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby, pp. 65. ↩︎

- Collins, The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby, pp. 65. ↩︎

- Collins, The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby, pp. 75. ↩︎

- Collins, The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby, pp. 71. ↩︎

- Garryowen FC, “Garryowen Rugby Club – Founded 1884,” Garryowen FC, September 13, 2025 <https://garryowenrugby.com/about/#history>. ↩︎

- Collins, The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby, pp. 79. ↩︎

- “LLandovery College Recognised as Co-Founder of Rugby in Wales – Llandovery RFC – Official Website,” June 26, 2024 <https://llandoveryrfc.co.uk/llandovery-college-recognised-as-co-founder-of-rugby-in-wales>. ↩︎

- There is evidence of a sport known as ‘cnapan’ in the West which seems to have predated rugby rules by centuries. ↩︎

- The Welsh were deemed to be far less of a threat than the Northern union to the RFU. Whilst it was imperative that the Welsh continued to play union to benefit the international game, there was simply not the number of teams (especially those of only a working class background) to threaten the governance to either the RFU or IRFB. ↩︎

- socialrightsireland, “To Celebrate the NFL Parachuting ‘Flag Football Starter Kits’ into Irish Schools as If It Were a Gift Is to Swallow US Cultural Imperialism Whole.,” Instagram, September 17, 2025 <https://www.instagram.com/p/DOs-IfljEsN/?hl=en>. ↩︎

- Richards, A Game for Hooligans, pp. 17. ↩︎

- Collins, The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby, pp. 317. ↩︎

- Jacob Bassford, “Tackling the World: A Public History of the First Women’s Rugby Union World Cup, 1991” (unpublished MA Thesis, University of York, 2025), pp. 29. ↩︎

- In the UK, women’s rugby has traditionally been centred on sports universities and polytecnics rather than traditional, “elite” universities. In comparison, the major rugby universities in North America are often considered ‘elite’, with the likes of Harvard providing a pipeline to the national team. ↩︎

- A discussion of class and the North/South divide can be found in the 1994 World Cup special episode of the podcast The Good, The Scaz and The Rugby featuring Northern rugby legend Gill Burns. Link: https://youtu.be/A6iP16IDHEE?si=KZntmEs0d6Tr74Kl ↩︎

- Anonymous in Bassford, “Tackling the World: A Public History of the First Women’s Rugby Union World Cup, 1991.”, pp. 33. ↩︎

- Wales is often seen in a derogatory manner by middle and upper class English people, dismissive attitudes towards the country stem from xenophobia and classism. ↩︎

- USA and Canada, to a lesser extent BUCs in Wales, Scotland and England. ↩︎

Leave a comment