In the 1920s, feminists took part in ‘Rugby Féminin’. However the controversial sport faced its demise a decade after its first match. Did barrette influence the female rugby players of the 1960s?

The origins of the modern women’s rugby movement can be traced to French universities during the 1960s. However, this was not the first time French women picked up an oval ball. Between 1922 and 1929, French feminists participated in barrette1, also known as rugby féminin, with the support of the same institution that promoted women’s association football in the country. Many have drawn connections between the two games; this article not only discusses the rise and fall of barrette in 1920s France, but also explores whether the development of women’s rugby in the 1960s can be linked to the earlier game.

The ‘roaring twenties’ is a well-known historical period in the Anglosphere, but France also had their own social revolution during the 1920s. Les Années folles was a period of social progressivism and positivity, and saw the birth of what is known as café society in Paris. Café society was the term used to describe the artists, musicians, and creative thinkers who gathered in cafés on the banks of the Seine. This scene was also filled with the last of the first wave of French feminists. Much like their Anglosphere counterparts, early French feminism was primarily concerned with women’s suffrage2. Along with this, many early French feminists were interested in expanding the roles and definition of womenhood in French society. One of the ways in which this was exercised was through sport.

The Féderation Féminine Sportives de France (FFSF), was co-founded and run by Alice Milliat3. Milliat was the pre-eminent advocate for women’s sports in France during the early nineteenth century, with her work culminating in the acceptance of female participation in Athletics in the Olympic Games4. Whilst the FFSF was not explicitly feminist, Milliat herself saw women’s sport as a feminist statement5. The FFSF was founded in 1928 when the French Athletics Federation refused to govern women’s sport; the new dedicated association covered a wide range of sports which would usually be considered ‘masculine’. The largest of the sports covered by the FFSF was football, but they also governed athletics, basketball, and swimming.

‘Women’s sports of all kinds are handicapped in my country by the lack of playing space. As we have no vote, we can not make our needs publicly felt, or bring pressure to bear in the right quarters. I always tell my girls that the vote is one of the things they will have to work for if France is to keep its place with other nations in the realm of feminine sport.’

-Alice Milliat, 19346

At Fémina Sport, an omnisport club based in Paris with links to and a shared leadership with FFSF, French men’s rugby international André Theuriet and physician Dr Marie Houdré came together to develop a contact sport for women in 1922. There were significant societal expectations and boundaries that hindered female athletes, even more so for female athletes playing a contact sport. Rugby in France has always been associated with masculinity, so women playing the sport would have negative connotations. Instead, Theuriet and Houdré looked towards another football code for inspiration.

Many countries and regions have folk football codes; France had a game known as barrette. Created in the South of France, the game was popularised in the late nineteenth century and was seen as a patriotic alternative to the English rugby union7. The sport had complex scoring requirements and was non-contact, but it did use an oval-shaped ball. Despite the codification of the rules in the 1890s, which allowed for national competition, the game quietly died out in favour of rugby. When Theuriet and Houdré were looking to develop a contact football game for women, they co-opted the name barrette.

The new version of barrette had few similarities to the original game; instead, it resembled rugby union. The new game was 12-a-side and had tackling, although only from the waist down8. Rugby historian Lydia Furse notes that the new game was designed to be a ‘watered-down version of rugby union, suitable for the weaker, sweeter sex.’9. Both versions, however, could be described as elegant, with an emphasis on passing rather than heavy contact and brute strength.

The first public game of barrette took place as a curtain raiser for the 1922 Fémina Sport women’s football final at the Stade Élisabeth10. Stade Élisabeth is still standing today and was a purpose-built stadium for women’s sport in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. Both teams had trained with Theuriet and had previously played private training matches against one another in preparation for their big game in front of thousands. Houdré captained the team in white11, and her opposition played in a ‘brightly coloured kit’12. Houdré was 39 and had been practicing as a doctor for just under a decade when she took part in the match13. Documents following the first match solidify the feminist origins of the new barrette, as Milliat wrote in a thank you note to leading feminist Jane Misme14: ‘In the future a tighter alliance will allow sportswomen to collaborate even more usefully for the feminist cause’15. In subsequent histories of barrette and women’s sport in France, Milliat’s feminist ideals are downplayed. Furse notes that the historians who have written those histories have primarily been male16.

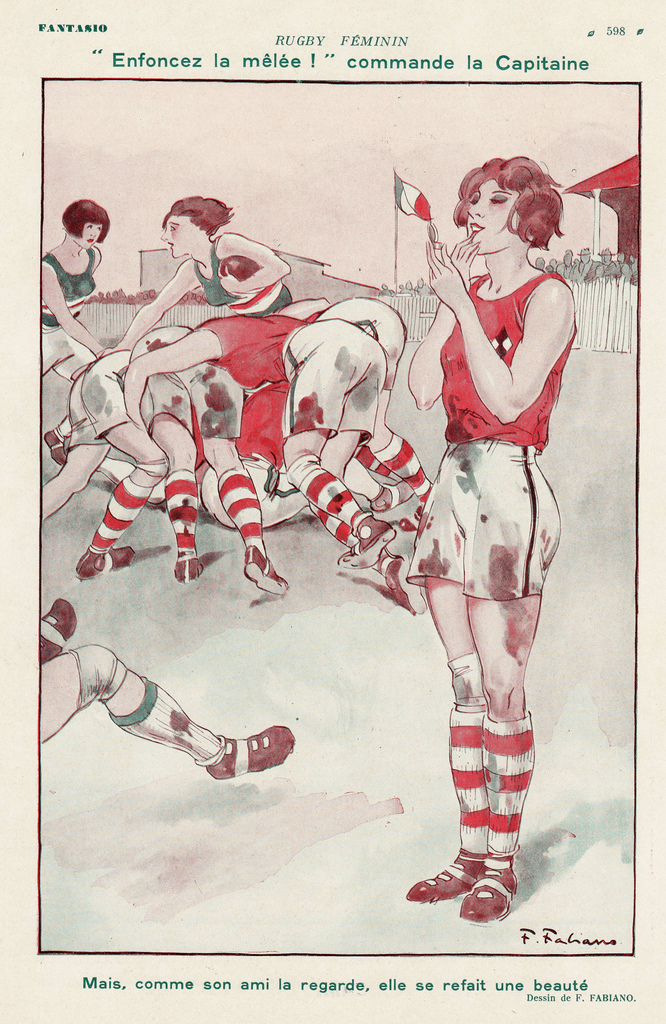

Despite the changes made to the game to make it more ‘suitable’ for women, the reactions to the game were no different than if they had not been made. Furse’s research shows that the media reaction to the game far outweighed the actual frequency of games being played. Between 1922 and 1924, only five games were played; this increased to nine games in 1926. However, if you went off of contemporary newspaper reports, you could easily be mistaken into believing that the game was widespread and played regularly. The newspaper La Presse were vocal critics of the game, going so far as to interview a doctor to comment on the ‘risks’ of women playing a contact sport. Professor Bergogonié, who had never seen a game of barrette, stated the game could in no way contribute to the ‘healthy development of a woman’17. Furse notes that in 1920s France, wider society saw the primary function of women as procreation and that the goal of women’s sports was to aid in the preparation of the female body and mind for motherhood. As barrette was a physical sport that carried a high injury risk, it was not seen as appropriate. Additionally, as barrette was seen as a masculine sport, players risked being seen as masculine by potential male suitors, which would prevent them from marrying. Newspapers, such as La Presse, frequently used the terms barrette and le rugby féminin interchangeably. By calling barrette “women’s rugby”, the sport was masculinised further and alienated the newspaper readers from the sport.

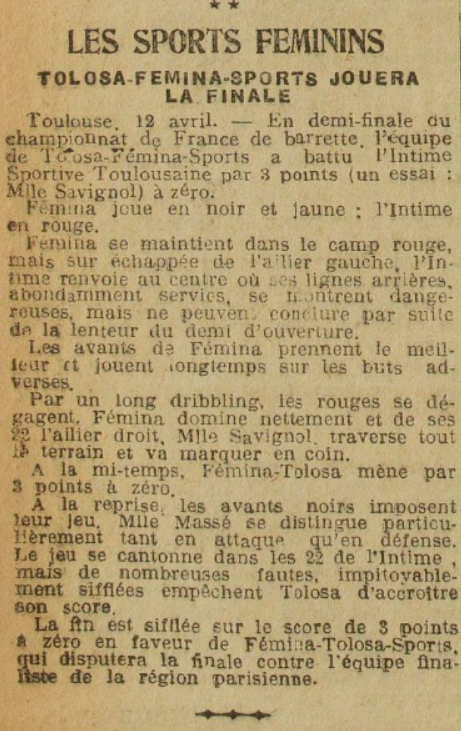

Despite a minuscule amount of games being played and the fact that barrette had primarily been played at a dedicated women’s sports stadium, fans and officials involved in men’s rugby felt that the sport could be a threat to rugby union. In a similar manner to the FA ban in England, which prohibited women’s football from being played at FA club grounds, the FFR banned barrette from being played at rugby union grounds in 192318. Those opposed to barrette celebrated, with La Presse writing ‘Women’s Rugby is Dead!’19. In 1927, Stade Français attempted to host a barrette match as a curtain raiser before the FFR championship game at their Stade Jean Bouin. This was the first major attempt to circumvent the ban, but unfortunately, the ban was upheld and the match was cancelled. Under the ban, the game and society had grown, with the reactions to the matches’ cancellation being significantly different to the pre-ban press coverage. ‘Why this ostracism? Will rugby pitches be desecrated by the steps of young girls? The oval ball is it so sacred that a femalehand commits, in touching it, a sacrilege?’20 wrote one journalist. ‘If there is a need to stop the spread of the female game, then reasons must be given’21 wrote another. The ban was not officially lifted in response, but matches were played prior to the Army v Paris Rugby Union matches in 1928 and 192922.

Whilst negative attitudes remained, the 1928 and 1929 matches produced positive and supportive news articles. In particular, a report in Match23 by René Del’Croix was extremely positive, with the leading line not unlike a 21st-century clickbait title24. The thorough article featured player portraits and a history of the game. It is clear, however, that Del’Croix understood the background of his readers and that they were of a certain social class. The narrative focused on how barrette was the ‘best’ of rugby without the brutality. Noting that the game was free-flowing, intelligent and elegant, he compared it to Les Années folles, a primarily middle class phenomenon. At the time, there were distinct class differences within French rugby. Whilst the sport in the South of France was played by all and was becoming an increasingly physical game which was rife with professionalisation25, the game in Paris was primarily played by the elite and was known for its speed and flair. By describing barrette as an intelligent and elegant game, Del’Croix was directly alluding to the ‘superior’ Parisian rugby of the elite.

The decline of the barrette movement follows the economic crash of 1929 and the rise of conservatism which followed. There are no match reports after May 1929, but women were still playing as late as 1935 at Fémina Sports26. 1930s France was significantly more conservative than the decade which had preceded it, and whilst barrette had come up against significant opposition in the 1920s, the transgressive and feminist nature of the sport made it almost impossible in the 1930s. Additionally, the FFSF suffered during the global economic crisis, with Milliat leaving in 1936 due to financial constraints within the organisation27. Furse speculates that the decline was also influenced by the expulsion of France from the Five Nations in 1931. She writes that with France out of the Five Nations28, the country moved towards rugby league as they were able to play test matches against the Northern Union. Rugby league was known as a faster game and deemed by commentators to be closer to the original game of barrette than rugby union. As league was now believed to be the true successor to barrette, and with league and barrette arguably having more similarities than union and barrette29, it was now deemed unsuitable for women to play barrette.

The final blow came to the game in 1941, as women’s rugby30 was banned by the Vichy government31. The role of women in Vichy France was strictly defined, with the promotion of ‘traditional’32 gender roles and an emphasis on childbearing. Whilst the Vichy government gave women the right to vote, they espoused a rigid definition of femininity. The originator of the ban was a woman named Marie-Thérèse Eyquem, who was the director of women’s sports under the Vichy regime. Eyquem had previously worked within Catholic organisations and could be described as the ideological opposite of Houdré. In an article with Tous les sports’s, Eyquem wrote:

‘[The development of women’s sports] occurred during the unstable post-war period. It is therefore unsurprising that during this period sportswomen over-masculinized themselves. They effectively did sport in the manner of men (violent sports– football, barrette– too competitive, too much aggression). And the public powers, attaching very little importance, for multiple reasons, to the physical education and sports of women, left them to develop and degenerate by chance.’

-Marie-Thérèse Eyquem, 13th December 194133

Under the Vichy regime, the role of women’s sports was solidified as the preparation of the female body and mind for motherhood. As such, ‘masculine’ sports such as rugby and football, which could ‘damage the womb’, were unsuitable in the conservative society.

The modern women’s rugby movement in France began in the 1960s with university students, with the first documented game taking place between Toulouse and Lyon34. The game spread across France quickly, and the first national championship was held in 197135. Today, it is common for barrette to be brought up in relation to the modern women’s rugby movement3637. However, despite the fact that both originated in France, there are no clear links between the two movements. Firstly, barrette was primarily played in Paris whilst the modern women’s rugby movement began in the the traditional rugby heartland of the South. Secondly, barrette distinctly had no links to rugby union clubs nor universities as it was administered in its entirety by the FFSF. Finally, it is unlikely that any of the female rugby players had personal links to barrette players. With four decades separating the two movements38, as well as geography, it is unlikely that there was any overlap.

The main link between barrette and women’s rugby union is the type of player who would’ve been attracted to the sports. Barrette was primarily played by those associated with the feminist movement and had the social power to play such a transgressive sport39. Similarly, 1960s women’s rugby players were young university students and, as such, were likely to be both progressive and from wealthier families. Any similarities between the styles of play between the two games are more likely due to the popularity40 of free-flowing French rugby rather than direct influence, as there are limited video recordings of barrette41.

Match footage begins around 27 seconds.

I hope you have enjoyed the fifth edition of The Rugby History Project. This will probably be my last post before the Women’s Rugby World Cup so I wanted to make sure I got some women’s rugby history in beforehand. Feedback and suggestions are welcomed as always.

-Hattie

Thanks for reading The Rugby History Project! Subscribe for free to receive new posts, or consider upgrading to Historian Tier to support the project!

- Also spelt Barette. ↩︎

- Which was achieved in 1944. ↩︎

- Lydia J. Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France,” The International Journal of the History of Sport, 36.11 (2019), pp. 941–58, doi:10.1080/09523367.2019.1634555, p. 942. ↩︎

- Mary Leigh and Thérèse Bonin, “The Pioneering Role Of Madame Alice Milliat and the FSFI* in Establishing International Trade and Field Competition for Women,” Journal of Sport History, 4.1 (1977), pp. 72–83, p. 72. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 942. ↩︎

- Milliat in Leigh and Bonin, “The Pioneering Role Of Madame Alice Milliat and the FSFI* in Establishing International Trade and Field Competition for Women.”, p. 76. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 943. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 944. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 944. ↩︎

- Anne-Emmanuelle Nettersheim, “EP 12 – Marie Houdré, the First to Score a Try in the World of Rugby,” TwoSixOne – Le Trail Running 100% Femmes, April 12, 2024 <https://twosixone.fr/en/blogs/261-legendes-du-sport-feminin/ep-12-marie-houdre-la-premiere-a-marquer-son-essai-dans-le-monde-du-rugby?srsltid=AfmBOoq5lNGbYeTb-nhkO0jSuRgwOnc7M-MA1cbLkApTQvitxyFpb2x8>. ↩︎

- Allianz Stadium, “Allez Les Bleus: Barrette Medal, 1928,” World Rugby Museum, February 27, 2023 <https://worldrugbymuseum.com/from-the-vaults/womens-rugby/barrette-medal-1928>. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 941. ↩︎

- Nettersheim, “EP 12 – Marie Houdré, the First to Score a Try in the World of Rugby.” ↩︎

- She had also donated the trophy for the women’s football final. ↩︎

- Milliat in Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 945. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 944. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 946-947. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 948. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 948. ↩︎

- Bastille in Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 948. ↩︎

- P. M. in Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 948. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 949. ↩︎

- The largest illustrated sports paper in France at the time. ↩︎

- ‘Pleasant, athletic, and fast, will barrette soon be women’s favourite sport?’ ↩︎

- Professionalism was required in the South of France as clubs relied on labourers as players. These working class players needed to recoup lost wages, not unlike their Welsh and Northern English counterparts. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 951. ↩︎

- Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 951. ↩︎

- Due to professionalism concerns raised by the RFU. ↩︎

- With fewer players and a more free-flowing game. ↩︎

- In any form. ↩︎

- Women’s football had previously been banned by the French Football Federation in 1933; this ban was upheld by the Vichy government. ↩︎

- ‘Traditional’ in the sense of an idealisation of nineteenth-century middle class history. ↩︎

- Eyquim in Furse, “Barrette: Le Rugby Féminin in 1920s France.”, p. 952. ↩︎

- Ali Donnelly, Scrum Queens (Pitch Publishing, 2020), pp. 35. ↩︎

- Donnelly, Scrum Queens, pp. 36. ↩︎

- Houdré was inducted to the French Rugby Hall of Fame in 2019. ↩︎

- Lydia Furse, “Pioneers of Women’s Rugby: Pre-1960,” ScrumQueens, May 16, 2020 <https://scrumqueens.com/features/pioneers-of-womens-rugby-pre-1960>. ↩︎

- Four decades would make it likely that the women were too young to be the daughters and too old to be the granddaughters of the original barrette players. ↩︎

- Middle class. ↩︎

- And frankly, stereotypes. ↩︎

- British Pathé, “PEACE AND PACE (1928),” YouTube, 1928 <https://youtu.be/xDNgo2E0osc> ↩︎

Leave a comment