For over a century, working class rugby players left Wales in order to be paid. However, for many men, “Going North” was a necessity as their skin colour was a barrier to rugby in Wales.

In June 2025, Billy Boston was honoured with a knighthood, becoming the first rugby league player to receive the nod1. In the same month, a book on Roy Francis, written by the legendary Tony Collins, was released. Whilst I was aware of Roy Francis and his incredible career, thanks to a Squidge Rugby video released in 20202, as well as being vaguely aware of the legacy of Welsh rugby union players who ‘broke the code’ and travelled to the North of England to play rugby league, I was not aware of the volume of players who broke the code. After Harry Bowen left Llanelli in 1884 to play for Dewsbury3, thousands of working class Welshmen left rugby union to be remunerated for their time. However, there was an undercurrent of racism and xenophobic discrimination within Welsh rugby union, which was sometimes an even bigger motivating factor in the decision to ‘Go North’.

‘I would have loved to play for Cardiff and I dreamt of playing for Wales, but it was never going to happen. A Black man was never going to play for Wales in those days. You can’t let it eat at you – you do the next best thing and go north.’

-Terry Michael, 20254

In 1895, representatives from twenty-two rugby clubs based in the North of England met at the George Hotel in Huddersfield, creating the Northern Rugby Football Union. This new union allowed “broken time” payments, compensation for time missed from work. The Rugby Football Union deemed broken time payments to be a form of professionalism and banned them in 1886. Upon the formation of the NRFU in 1895, all clubs and players associated with the NRFU were banned from RFU competitions. This great schism would go on to be the foundation of the sports of rugby union and rugby league, as well as solidifying the class associations with each of the two sports. Despite Wales having more in common economically with the North of England than the RFU’s heartland of Southern England, the WRU followed the RFU’s lead when it came to professionalisation5. Rugby in Wales crossed class boundaries, but amateurism left working class men at a disadvantage, and many were unable to support their families due to the amount of work missed and resulting docked wages. It is likely that the number of Welshmen who traveled North over the course of a century to receive broken time payments is well into the thousands. However, for some who went North, broken time payments were not the only motivating factor.

As a port city, Cardiff has long been an ethnically diverse place. With a large Black community, the city also has long standing Italian and Irish communities. Cardiff is also not the only place in Wales with a long history of immigration, with Newport having large Black, Chinese, and Greek communities, and mining communities were also a major attraction for immigrants during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Despite this, rugby union has not always represented the whole of Wales. It was an open secret in Welsh rugby union that Black men would not be selected to represent their nation, with the first Black player to break the informal colour bar being Mark Brown in 198367. On top of this, in the early 1900s it was not unheard of for the Welsh Rugby Union to change white players’ names to make the team appear more ‘Welsh’. Cardiff and Wales international William O’Neill had his name recorded by the WRU as Billy Neil between 1904 and 1908 as a way to hide his Irish heritage, something which O’Neill reportedly found deeply offensive8. O’Neill would be one of the first to sign for a Northern team after professionalisation, where his surname was proudly recorded as O’Neill. Further still, Black players had little opportunity to play club rugby, let alone a chance to play international rugby. Whilst smaller clubs such as Cardiff Internationals Athletic Club, based in Tiger Bay, had sides which represented the Cardiff community, larger clubs such as Cardiff RFC were overwhelmingly white9. With this in mind, it became increasingly popular during the twentieth century for those players who faced discrimination within Welsh rugby union to go North and play rugby league.

Rugby historian Tony Collins has argued that the working class origins of rugby league allowed for a more egalitarian culture within the sport in comparison to rugby union10. Founded on the basis of equality for all players, the first Black player known to sign a professional contract was American Lucius Banks for Hunslet in 1912. He was shortly followed by Jimmy Peters, who signed for Barrow in 191311. Peters has been celebrated by the English rugby union community in recent years, as he was the first Black player to represent England12; however, he left the sport following a series of issues. After facing non-selection due to his race at both club and international levels, Peters was suspended for allegedly accepting payment. Banks’ career would only last a year, and World War One would go on to end Peters’s, but their legacy would continue in the interwar period.

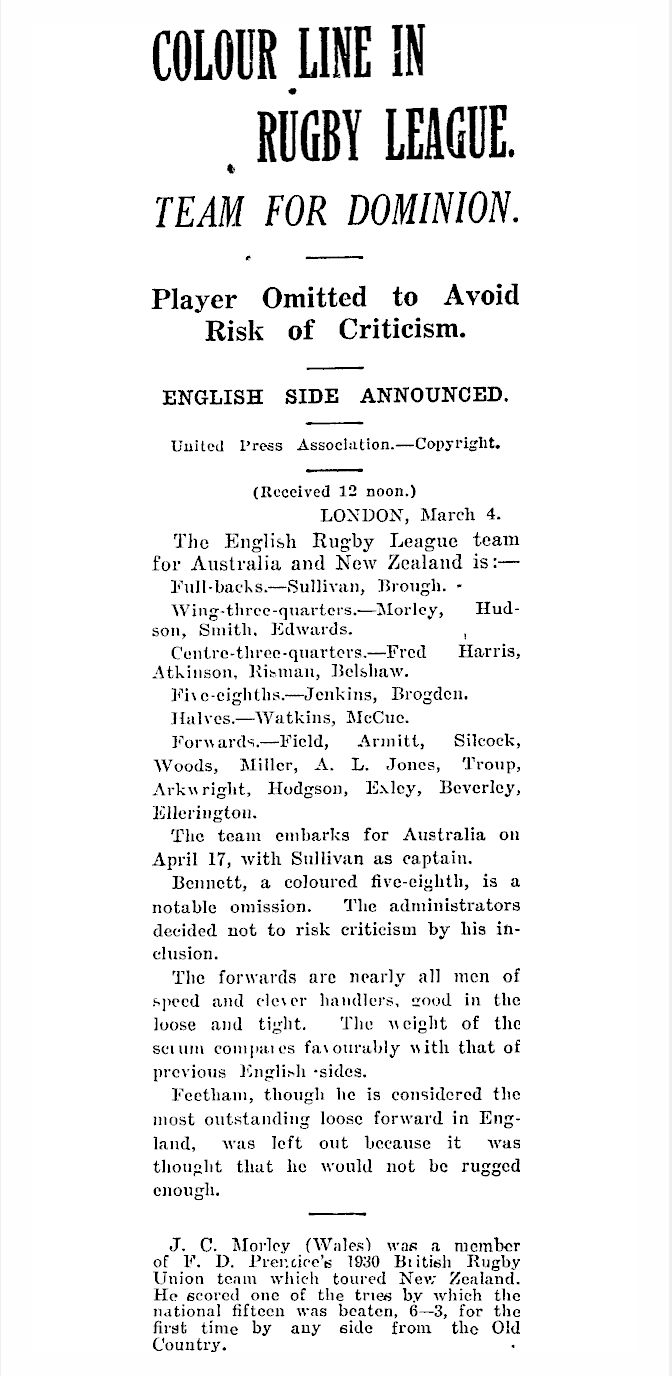

It is not known who was the first Black Welshman to play rugby league, but George Bennett was the first Black player to represent Wales in the sport13 and would prove to be an aspirational story for other Black Welsh rugby players. Born in Forden, Montgomeryshire in 1913, Bennett signed for Wigan at the age of just 17. Bennett specifically cited racism in Welsh rugby union as a significant contributing factor in his decision14. Bennett would go on to play 383 games across two clubs during his career. He would also feature in Wales’ first-ever rugby league international in 193515, in the process becoming the first Black player to represent any British international side in rugby league. However, despite the acceptance of his race within his club settings and within Welsh rugby league, Bennett was a noted exception in the 1936 Great Britain tour of Australia. The official reason given for his omission was ‘to avoid risk of criticism’16 due to Australia’s strict colour bar, and unfortunately, he would not be the only Black Welsh player to be omitted from a Great Britain side due to his race.

‘He stood tall, proud and stoic through all life’s challenges. He went on to be a leader of men, white men, during a time when most of wider society would not tolerate his existence’

-Martin Offiah, 202517

Roy Francis is one of the most iconic names in rugby league history; despite this, he is not particularly well known nor recognised within Welsh sporting history. A legendary player who represented Wales, England, and Great Britain, he would go on to revolutionise league coaching during a period when coaches weren’t even considered essential18. All of his achievements would be remarkable and noteworthy if he had been a born and bred rugby league player from the North of England, but he was actually an illegitimate mixed-race Welshman from Brynmawr who left Welsh rugby union behind to escape institutional racism.

Roy Francis’ life is one of the most interesting yet heartbreaking tales in rugby. Born to a teenage white mother and a middle-aged Black father in a maternity hospital for illegitimate children in Tiger Bay in January 1919, he was adopted as a young child by his father’s estranged wife, Rebecca Francis, and raised in Brynmawr19. Brynmawr had a vibrant Black community at the time20, including at the local rugby club. Making his debut for his village’s senior side shortly after his seventeenth birthday, Francis was approached by a scout from Wigan after his third game21. League scouts were not unusual in South Wales at the time22, and those who were either excluded from international representation or those looking for financial stability were easy targets. The unemployment rate for Black men in Cardiff during the mid-1930s was estimated at the time to sit at around 80%23. For Black rugby players in South Wales, the opportunity to be remunerated for their time, possibly secure a job through club connections, and have the chance to represent their nation on an international stage made the choice clear. After playing in an amateur game for Wigan A under the name A. N. Other, Francis signed for Wigan for £400 in November 193624.

Wigan was an overwhelmingly white town, with the only recorded people of colour living there at the time being Francis’s teammates George Bennett and Len Mason2526. Francis’s time in Wigan was challenging. Whilst he met and married his wife, Rene, in 1938, he struggled with secretary-manager Harry Sunderland, who joined the club in October of that year. Sunderland was from Australia, a country with a strict colour bar. The White Australia policy blocked non-European immigration to the country27, whilst Indigenous Australians faced severe discrimination at all levels. Sunderland’s views were extreme even for an average white Australian28, and it is not surprising that Francis’s playing time suffered under him. Francis would play only three first-team matches under Sunderland’s watch, being relegated to Wigan’s A team despite being a fan favourite due to his try-scoring rate29. The relationship between the two deeply affected Francis, who reflected on his experience by saying, ‘Racialism is like a pain. It is a very, very personal thing.’30 Roy was transferred to Barrow for £450 in January 1939, after being told by Sunderland, ‘I can’t be doing with you.’31

We likely lost out on the prime of Francis’s playing career due to World War Two. He enlisted on the 16th October 193932 and spent the entirety of his war service in England. This is probably because he had been promoted to sergeant very quickly, and it would have been seen by those higher up as giving the wrong impression for those overseas to see a Black man in a position of power. Whilst serving, he underwent physical education training, something which would become incredibly useful later in his career33. The rules around amateurism and professionalism were abandoned for servicemen in Britain during the war, and many rugby players played both codes of rugby. Francis himself played club rugby league before being called up to play interservices rugby union for England. Despite the fact that Francis was not English and that he had been called up to play interservices rugby league for Wales at the same time, due to hierarchies, he was required to answer the England call-up34. Before his second match, Francis faced one of his most infamous and public displays of discrimination as he was refused entry to the Welford Road changing rooms by security for over an hour, with the men not believing that a Black man would be playing for England35. It is also interesting to note that whilst other rugby league players were called up to play union for the Welsh representative side during the war period, Francis was never considered by Welsh selectors.

In January 1946, upon the conclusion of the war and ten years after George Bennett’s exclusion from a British touring side, Francis was excluded from the 1946 Great Britain Rugby League side, which was due to tour Australia. Whilst Francis’s form had dipped in 1945 following an injury, he was still regarded as one of the best wingers in Britain. A year later, Francis would debut for Great Britain, the first Black player to do so, scoring two tries in the process and producing the only known footage of Francis during his playing days. However, it would be on home soil. And the footage would be of him celebrating a white player scoring36.

The remainder of Francis’s playing career would be split between Barrow, Warrington, and Hull FC, retiring in 1954 having played 346 club games and scoring 225 tries37. The last four years of Francis’s playing career would be spent as a player-coach at Hull FC. From the start of his coaching career, he was innovative, from providing his players with running spikes to pre-season training and film reviews38. Whilst this may sound like incredibly simple and basic coaching practices in 2025, in the 1950s, it was not unusual for teams to not even have a full-time coach39, with club directors making team sheet decisions and captains leading coaching sessions. Whilst Francis had been the unofficial coach from the 1950 season, he signed an official player-coach contract in 1951 and retained his coaching position upon his playing retirement in 195440. By signing his coaching contract, he became Britain’s first-ever Black professional sports coach41.

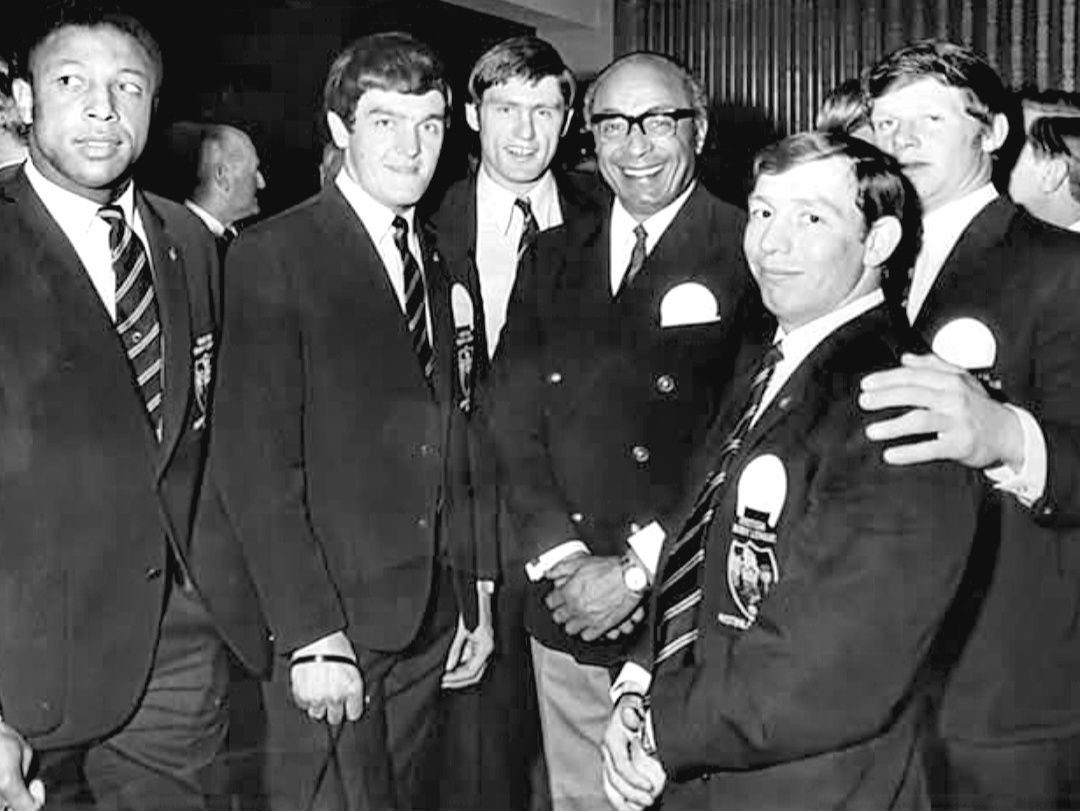

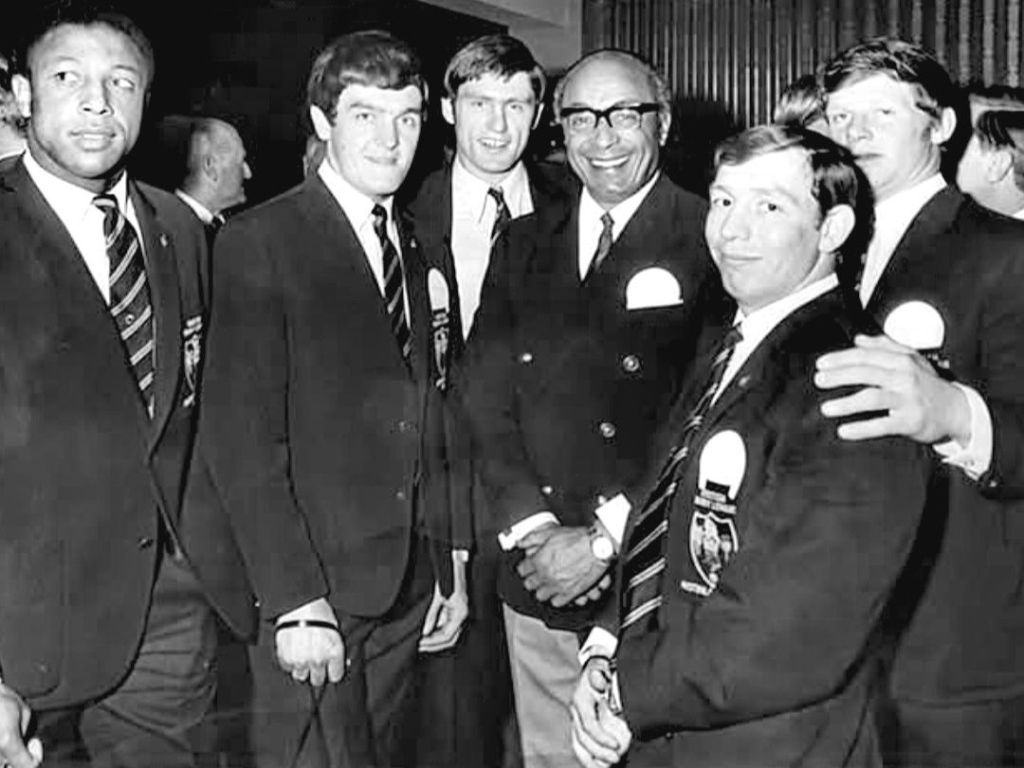

In Britain, Francis would become one of the most successful rugby league coaches of all time. Winning the Championship twice with Hull and once with Leeds, he would also win the Challenge Cup with Leeds in 196842. He was also successful in providing a healthy environment for his players, encouraging a family atmosphere, and acting as a father figure to many players43. The mutual respect he had with players and his even-keeled attitude was reflective of how Francis wished to be treated by others, with Collins noting that the ‘withholding of dignity and respect is at the dehumanising core of racism’44. It cannot be overstated how beloved Francis was by his players, with the majority of the opposition to his coaching revolving around his need for complete control of his teams. This control was not only a coaching method; Francis’s carefully controlled environment also protected him from racism. Unbeknownst to many of those around him, Francis suffered from mental health issues45, which resulted in a three-week hospital stay in 196146. Whilst many former players have often quipped that they didn’t see Francis’s race, this is dismissive of his experiences and also perpetuates negative stereotypes of Black men. Roy Francis was a successful Black man in a position of power in 1950s and 60s, a Black man who was a leader of white men. This was not done without struggle or prejudice.

‘No Black man can hope ever to be entirely liberated from this eternal warfare’

-James Baldwin

Whilst Francis maintained a well-controlled environment in Britain and rarely faced overt racism from the press or management, his short stint coaching North Sydney laid bare the true attitudes of many at the time. During an initial six-week stint as an associate in 1968, he was extremely successful with an almost permanently struggling team. Management had initially been unaware that Francis was Black when they had hired him, and whilst chairman Harry McKinnon didn’t take issue47, the team’s head coach was former Springbok Col Greenwood, a noted supporter of his home nation’s Apartheid regime48. Initial media reports were positive49, but after Francis became head coach in late 1969, the media coverage developed a racist edge. Described as a ‘witch doctor’ ‘casting spells’50 and compared to Malcolm X51, Francis was hounded by the press to a degree he had not faced in Britain. He also faced so-called ‘casual racism’ from the public, resulting in him becoming reclusive52. His wife Rene, became incredibly concerned about her husband’s well-being, fearing a repeat of his 1961 hospitalisation.

‘I’m bringing him home. They are crucifying him and he’s going to have a nervous breakdown.’

-Rene Francis in a letter to her sons, March 1971

Francis ended up leaving before the start of the 1971 season, a decision which was accepted by North Sydney management and welcomed by the press.

‘When all of your critics are through dealing with you, Mr Francis, Sydney will be only too willing to forget you. Unfortunate but true. You are coloured, you see, Mr Francis, and even if you were the reincarnation of Dally Messenger, you would not have made it in the small world that is Sydney Rugby League.’

-Sydney Journalist, 197153

Francis returned to England, but he was never quite the same after his stay in Australia. Aside from winning a Championship with Leeds in 1974, his later life was marred by heavy drinking and health issues. Roy passed away on the 5th April 1989, twelve years after retiring entirely from rugby.

Whilst the RFL had hidden behind the White Australia policy in 1936 and 1946, in 1954 selectors were unable to ignore an 19-year-old from Tiger Bay. Billy Boston was born on the 6th August 1934 to a Sierra Leonean father and a Welsh-Irish mother54 and was the middle of eleven children55. Raised by the Cardiff Docks, Boston first achieved local fame playing for Cardiff Internationals Athletic Club, a newly formed, diverse club close to his home56. After representing Wales in various youth sides57, Boston should’ve been a hot commodity, and, despite being born and bred in Cardiff, Boston was not considered by Cardiff RFC. The legendary club had previously passed on Black players Johnny Freeman and Colin Dixon58. He did, however, catch the eyes of Neath in 1950. In a cruel twist of fate, the journey to Neath required Boston to catch a bus from outside the Arms Park59, but he was allegedly slipped £5 after every game for Neath as boot money60. Speaking later in life, Boston talked about his snub from Cardiff and had reportedly long accepted that his skin tone probably played a part.

‘I would’ve loved to play for Cardiff but it never happened so thats it. I don’t know what it was but they didn’t seem to think I was good enough so there you are… They made a mistake, not me.’

-Billy Boston, 201861

At the age of 18, Boston was called to complete his National Service in Catterick, North Yorkshire. He was quickly picked up to play interservices rugby union for both his unit and the Army, appearing at the legendary Army v Navy match at Twickenham62. Boston also continued to appear for Neath whenever he was on leave, and it was during one of these weekends that scouts caught him at his parents house. Acting as an unofficial agent, his mother Nellie negotiated for a £3000 signing-on fee with Wigan chairman Joe Taylor in her front room. Initially offered £1000, and then £1500, Mrs. Boston told Taylor that they would consider £3000. Luckily for Mrs. Boston, Taylor had withdrawn £3000 from the bank63. Her son had been unsure of signing the contract, and later he confided in a reporter that he had cried that night, as signing the contract meant he would be banned from ever playing for Cardiff or Wales.

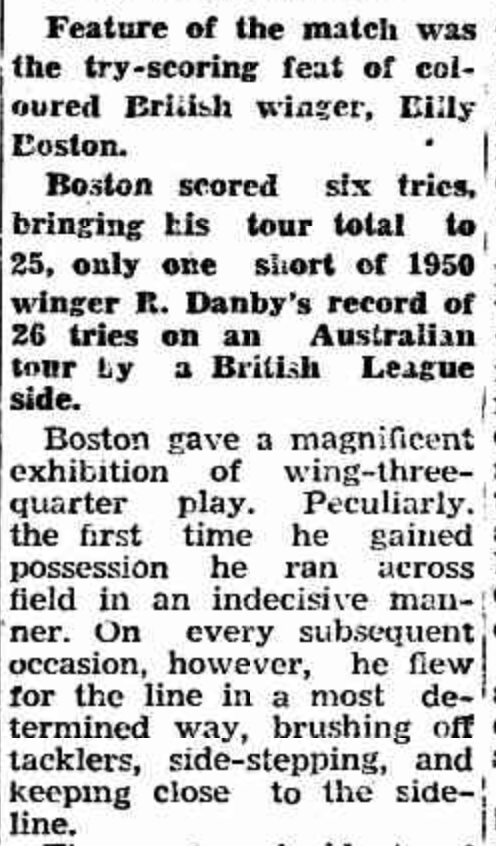

Whilst Boston himself thought that his £3000 signing-on fee was excessive, it would ultimately pay off for Wigan. Boston would go on to not only become a Wigan legend but would also become known as one of the best players to have ever played the game. During his illustrious career, he scored 571 tries in 564 rugby league matches64, making him the second-highest try scorer in rugby league history. Unlike Francis, who not only had to wait for his Great Britain debut but also spent a considerable amount of time playing for Wigan’s A team, Boston made an immediate impact with Wigan after playing his first game in November 1953. Boston’s fast start with Wigan also caught the eyes of Great Britain selectors, and he travelled to Australia and New Zealand with the invitational side mere months after switching codes. In doing so, he became the first Black British player to tour Australia65.

Despite missing the first test against Australia66, Boston would star throughout the tour. Scoring six tries in the five tests he played, he scored a total of 36 tries in eighteen games across the tour67, including four tries each against Wide Bay, North Queensland, Canterbury, and in the first test against New Zealand. He also scored a whopping six tries against Northern NSW.

Regardless of Boston’s success and record-breaking feats in both his club and invitational sides, he still faced discrimination within rugby league. In 1956, Boston was suspended following Wigan’s semi-final loss and forced to write a letter of apology to the club board. Boston had played the game both injured and out of position, but the most upsetting thing to the board members was that Boston had been late to report to the changing room before the match. Boston hadn’t been late for superfluous reasons; he had been helping his heavily pregnant wife to her seat68. Boston had been blamed for the loss over any other player, and it is not difficult to see why he had been blamed as a Black man in 1950s Britain.

‘It’s difficult not to draw the conclusion that the directors needed a scapegoat, and the stereotype of the lazy, undisciplined Black man made it easy for them to blame Billy.’

-Tony Collins, 202569

Boston, however, often faced overt acts of racism head-on. One well-known example is when he faced racist heckling from a Swinton fan in 1964. Rather than ignore the racist remarks from the fan, which Roy Francis had often done, Boston decided to enter the stands and confront the Swinton fan, who swiftly ran from the area rather than face the athlete he had abused70. He had previously also twice refused to travel to South Africa with Great Britain71. Touring South Africa would’ve required Boston to be segregated from his teammates: staying in a different hotel, taking different transport, and eating in different restaurants72. He also inevitably would’ve faced racist abuse from the crowds and by South African players if he had been selected to play.

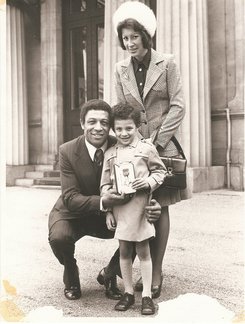

Boston retired in 1970, playing one season for Blackpool Borough73 after fifteen years in Wigan. Remembered by many dual-code Welsh players as a legend74, much of the recognition of his legendary career has come in the last decade. Despite his prowess with the Great Britain side, Boston never played a full test match for Wales. In 2016, he was awarded a legacy cap by Wales Rugby League in recognition of the single non-test match he played7576. Boston has also been honoured with various statues, including one just a stone’s throw from where he grew up in Cardiff77. The largest of all the honours awarded to Boston is the knighthood he received in June 2025, following a campaign backed by MP for Wigan and current Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy78. With this honour, he became the first rugby league player to be knighted for services to sport7980. However, in a cruel twist of fate, Boston was diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2016, before the majority of the recognition of his career outside of rugby league circles81.

‘All I have achieved in rugby league I would have given over for just one Welsh [rugby union] cap. That was my biggest ambition. I always wanted to play for Wales and I went to Neath because Cardiff didn’t want to know me but it’s worked out for the best. There was a lot of colour prejudice at the time and I don’t think I would have ever played for Wales in those days. I never wanted to sign for rugby league, but I saw the doors weren’t open here and there were no signs I would ever get anything.

I hope there’s a lot of people from the Docks that make it and don’t have the obstacles I had to face.’

-Billy Boston, speaking to the South Wales Echo82

Clive Sullivan’s journey to rugby league was significantly different from Francis’s and Boston’s, but without their contributions, Sullivan’s career may not have been possible. Sullivan’s background was similar, like Francis he was raised by a Black single mother, and like Boston he was raised in Cardiff. However unlike them, he was not a childhood rugby superstar. Whilst Francis was the first Black player to play for Great Britain and Boston was the first Black player to tour with Great Britain, Sullivan would become the first Black player to captain a British international side in any major sport.

Sullivan was born in April 1943 in Cardiff to Caribbean parents; his mother was of Antiguan descent, whilst his father was Jamaican. His parents split up when he was young and his mother raised him first in Splott before moving to Ely83. All four of the Sullivan children were renowned for their sprinting prowess from a very young age84 and after moving schools, both Clive and his elder brother Brian transitioned to playing rugby union85. Clive in particular looked up to local rugby league superstar Billy Boston86. A typical younger brother, Sullivan was obsessive in attempting to surpass the skills of his older brother, but he faced severe injury issues as a teenager. A serious thigh sprain, reportedly caused by overuse during a growth spurt, resulted in him being in a cast for six months87 and barely able to walk for two years88. Despite having had a promising youth career, complete with Cardiff Schoolboys caps89, Sullivan gave up playing rugby.

At eighteen, after a short-lived career as a mechanic, Sullivan joined the army and was posted to Catterick, North Yorkshire, to work as a radio operator90. Accounts of what happened next are slightly fuzzy, but it seems that Sullivan was picked to play for the regiment’s rugby union team by selectors who assumed Sullivan knew how to play on account of being Welsh91. Sullivan was unable to tell the army about his leg injury, as this would’ve resulted in a dismissal, so he decided to play the match. Sullivan ended up impressing on the wing and proved to himself that he could still play the game that he loved92, so he carried on playing in interservices matches. Rugby union matches in Yorkshire were regularly attended by rugby league scouts93. Sullivan was spotted by these scouts and picked up to play in a Bradford Northern A team match. Unfortunately, this trial was unsuccessful, but a chance encounter at a bus stop after the match would lead to a signed contract and the start of a legacy.

Touch judge Jimmy Harker, a Hull FC insider, spotted Sullivan in his fatigues waiting at the bus stop and gave him a lift to the train station. After a quick chat, Harker promised to speak to the board94. After a game of cat and mouse95, Sullivan debuted for Hull on 9th December 1961. His hat-trick led to a panicked scramble as Hull quickly sought to get him officially signed. Luckily for the Hull board, coach Roy Francis took Sullivan to his house to spend the night. He officially signed his contract on the 10th December96. The first two years of his career were spent under Francis, and despite missing periods due to his army service and injuries sustained in a serious car accident in 19639798, Sullivan developed into a great player under Francis’s watchful eye. Francis’s influence can also be seen in how Sullivan dealt with racist abuse from spectators, as he often brushed off the abuse and used his talents to prove his worth rather than engage in confrontation99. Sullivan’s widow told his biographer James Oddy decades later that ‘Roy took Clive under his wing. I didn’t know Clive then, [but] he stayed with the Francis family. His wife was really good to Clive.’100

Sullivan’s career was plagued with injuries, including an incredibly rare thigh condition which caused his muscles to calcify and attach themselves to the bone101. Despite the frequent missed time, his high strike rate and incredible reputation not only earned him the Hull FC captaincy but also kept him in contention for international honours. He was selected for Great Britain for two games against France in 1967 and grabbed a hat-trick against New Zealand in the 1968 World Cup102. With his selection in 1967, he became the first Black player to be selected to represent Great Britain since Billy Boston103. Sullivan, however, would go one better than his former coach Francis, or his childhood hero Boston: he would become the first Black athlete to captain a British international sports team104.

The 1972 Great Britain season would pose serious issues for selectors due to a controversial brawl in the 1970 final and widespread injuries which took out the majority of captaincy options. With two warm-up matches played prior to the tournament, Great Britain management selected Sullivan to captain the first match due to his captaincy experience. The team sustained more injuries in that match and so he also captained the second match. By captaining these matches, Sullivan became the first Black captain of any British international team in a major sport105. The importance of this achievement has only been celebrated recently, but it is even more impressive due to the fact that the Welsh Rugby Union team wouldn’t even cap a Black player until over a decade later. Following the success of his first two outings as captain, Sullivan was not only selected to play in the 1972 World Cup, but also to captain the team.

‘I had hoped I would be selected, but the news still came as a marvellous surprise. I have been quite pleased with my game this season.’

-Clive Sullivan, 1972106

The World Cup was held in France and featured only four teams. The round robin saw Great Britain go undefeated and they faced Australia in the final. The French supporters, who had expected to reach the final, did not turn up in Lyon and the game was played in front of only 4000 people107. Great Britain also couldn’t afford to fly out the teams families for the event, and neither could the players108, which led to a poor atmosphere from the crowd. Despite this, both teams put in incredible performances and nothing could separate the two. Literally. The match ended in a 10-10 draw. However, as Great Britain had won the teams round robin match 27-21, they were awarded the World Cup109. Clive Sullivan lifted the trophy, but those back home in Britain were not watching as the BBC decided not to air the final live due to the violence at the 1970 World Cup. The French league officials also decided not to give out medals, perhaps due to sour grapes from failing to reach the final. Back home, there was not much of a fan fare either. Sullivan received an MBE for his achievement as captain and also appeared on an episode of “This is Your Life” but otherwise he faded into insignificance outside of rugby league circles110.

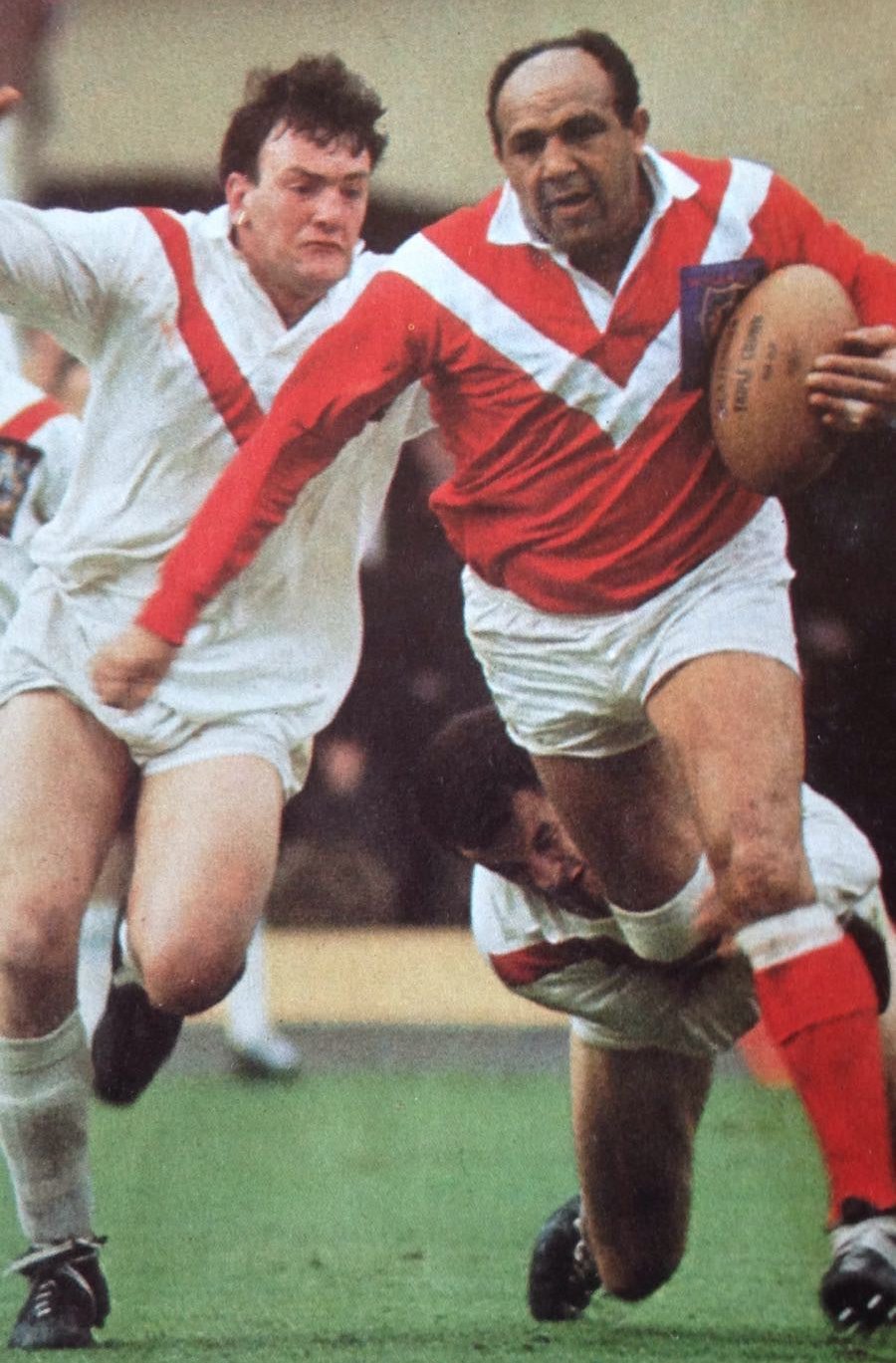

Sullivan would go on to spend two more unsuccessful seasons at Hull FC, interspersed with Wales Rugby League caps. Despite being a club legend who was known for his community outreach, his time at Hull was not fruitful and he only managed to win a singular Yorkshire Cup. Due to backroom issues at Hull FC, Sullivan decided to leave the club in 1974. He was however an adopted Hull man at heart, and with a growing family, he decided to stay in the city and switch to Hull FC’s arch rivals: Hull Kingston Rovers. With Hull KR, Sullivan finally achieved the pinnacle of British rugby league: winning a Challenge Cup final at Wembley in 1980 at the age of 37111. Heading towards the twilight of his career, Sullivan returned to Hull FC as a player- coach in 1981112113. In his first season back he managed to pick up a second Challenge Cup final winner’s medal, after starring in a rematch held in Leeds114.

The Challenge Cup rematch would turn out to be the last of Sullivan’s big games, he did however turn out for both Hull and Doncaster over the next two years115. By doing such he became the oldest ever player in a top flight match, and of course the oldest ever try scorer too. His primary focus however was coaching, acting as head coach at Doncaster and an assistant coach at Hull, before retiring from professional sport entirely ahead of the 1984-85 season. Using his connections, he opened a sports bar called Sully’s, which of course had an amateur rugby league side affiliated with it116. It was whilst playing for this team in April 1985 that he fell awkwardly on his back. The pain however did not subside, leading him to see a doctor. Two weeks after the match, Sullivan was diagnosed with an aggressive form of liver cancer117. Despite undertaking chemotherapy and vowing to fight the disease, Sullivan died on the 8th October 1985 aged just 42118.

‘I used to say “you’d die without your rugby.” It was said as a joke. But I can’t put into words how much he loved the game. That was Clive. … And he did die without his rugby.’

-Rosalyn Sullivan119

The legacies of all three of these men varies widely. In Hull, Clive Sullivan Way is the main road into the city120, Billy Boston has a large statue outside Wigan’s home ground121 and Roy Francis has a statue in Brynmawr122. Sullivan and Boston also feature in a large statue in Cardiff Bay, along with former Wales and Great Britain captain Gus Risman123124. Francis’s name sits on the base of the statue. Francis, Boston and Sullivan were far from the only Black Welsh players to go North, but each of the trio achieved groundbreaking firsts as well as having under-recognised careers. All three of these men125 deserved to achieve their dream of playing for the Welsh Rugby Union team, but due to the colour of their skin they were never even in contention.

Whilst the statues in Wales and documentaries around the Welsh lost generations finally give the three men an ounce of the recognition they deserve, their true legacy lies in those who have followed. The most poetic of careers belongs to Anthony Sullivan, the son of Clive. Not only did the younger Sullivan play for Hull KR and St. Helens, he also represented both Wales and Great Britain in rugby league. Following the professionalisation of the rugby union in 1995, he broke the code. With his switch, Anthony achieved something Francis, Boston and Sullivan Sr. had dreamed of doing but were excluded from due to their race: playing for Cardiff RFC and the Welsh National Rugby Union team126.

Francis, Boston and Sullivan were all on the receiving end of institutional racism as well as racist attacks whilst playing. Despite their talent and success, all three men were judged according to their skin colour first and fought against prejudice. This abuse was a direct reflection of the society in which they lived127. Whilst they all had their own experiences and ways of handling it, the prejudice that they faced was a direct affront to the men’s dignity and humanity. To paraphrase Tony Collins, whose book on Roy Francis was invaluable in the writing of this article, the sad truth is that respect and dignity can not be guaranteed to Black men in a racist society.

I hope you have enjoyed the fourth edition of The Rugby History Project. This has been a real rollercoaster to write and it has ended up being longer than my undergraduate dissertation. I’m no rugby league expert but I felt these stories needed to be told in the context of Welsh rugby. References and notations can be found below.

-Hattie

Thanks for reading The Rugby History Project! Subscribe for free to receive new posts, or consider upgrading to Historian Tier to support the project!

- Sky Sports, “Billy Boston: First Non-White Player to Represent Great Britain on a Lions Tour Receives Rugby League’s First Knighthood,” Sky Sports, June 11, 2025 <https://www.skysports.com/rugby-league/news/12215/13381499/billy-boston-first-non-white-player-to-represent-great-britain-on-a-lions-tour-to-receive-rugby-leagues-first-knighthood>. ↩︎

- Squidge Rugby, “So Who Was Roy Francis? | A Squidge Rugby Deep Dive,” YouTube, June 14, 2020 <https://youtu.be/FRX27awOb6g?si=oZTcwx2l7eKuOT5M> ↩︎

- Tony Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader (London: Bloomsbury Sport, 2019), pp. 25. ↩︎

- Michael, Terry in Carolyn Hitt, “The Lost Welsh Rugby Heroes Who Never Got to Play Union for Wales Because They Were Black,” Wales Online, May 16, 2020 <https://www.walesonline.co.uk/sport/rugby/rugby-news/the-rugby-codebreakers-billy-boston-14391534>. ↩︎

- At least in theory… In reality, many Welsh union players received “boot money”. ↩︎

- BBC, “The Rugby Code Breakers,” YouTube, August 18, 2018 <https://youtu.be/Lo8nAtxhUl0?si=OydSTLuuvJOfSoKp> ↩︎

- Glen Webbe is often misattributed to being the first Black Welshman to be capped in rugby union, but Mark Brown (who had a Jamaican father and English mother) was capped three years before Webbe’s first cap. ↩︎

- BBC, “The Rugby Code Breakers.” ↩︎

- Collins, Tony in ITV Sport, “Exiles to Icons: The Codebreakers Come Home | Careers of Billy Boston, Clive Sullivan & Gus Risman,” YouTube, July 28, 2023 <https://youtu.be/vzUXJhD1t2U?si=LqkPZxLyMRL_l6Lv> ↩︎

- Tony Collins, “The Black Pioneers of Rugby League,” August 27, 2020 <https://www.rugby-league.com/article/23664/the-black-pioneers-of-rugby-league>. ↩︎

- Collins, “The Black Pioneers of Rugby League.” ↩︎

- And the only until 1988. ↩︎

- Paul Blackledge, “The Struggle and the Scrum,” International Socialism, April 10, 2007 <https://isj.org.uk/the-struggle-and-the-scrum/>. ↩︎

- Blackledge, “The Struggle and the Scrum.” ↩︎

- Elizabeth Birt, “Rugby League: Wales’ First Black Players from Risca and Newport,” South Wales Argus, October 4, 2020 <https://www.southwalesargus.co.uk/news/18769551.rugby-league-wales-first-black-players-risca-newport/>. ↩︎

- United Press Association, “Colour Line in Rugby League,” Auckland Star (Auckland Star, March 4, 1936) <https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19360305.2.64#print>. ↩︎

- Offiah, Martin in Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 0. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 84. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 6-10. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 14. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 23. ↩︎

- BBC, “The Rugby Code Breakers.” ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 15. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 23-24. ↩︎

- Mason was Māori. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 28. ↩︎

- With the exclusion of Māori, a reluctant choice on behalf of the Australian government, necessitated due to the fact Māori had the right to vote in New Zealand. ↩︎

- Sunderland wrote in his Brisbane Telegraph column in July 1939 ‘Beethoven! Hitler! Röntgen! Diesel! Wagner! How sad it is that there are not more Germans like them.’ ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 39. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 40. ↩︎

- Sunderland in Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 39. ↩︎

- Three days prior to the lifting of the colour bar. ↩︎

- Squidge Rugby, “So Who Was Roy Francis? | A Squidge Rugby Deep Dive.” ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 56. ↩︎

- Squidge Rugby, “So Who Was Roy Francis? | A Squidge Rugby Deep Dive.” ↩︎

- Squidge Rugby, “So Who Was Roy Francis? | A Squidge Rugby Deep Dive.” ↩︎

- Wikipedia contributors, “Roy Francis (Rugby),” Wikipedia, June 10, 2025 <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Francis_(rugby)>. ↩︎

- Squidge Rugby, “So Who Was Roy Francis? | A Squidge Rugby Deep Dive.” ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 84. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 97. ↩︎

- BBC, “The Rugby Code Breakers.” ↩︎

- Something he had failed to win with Hull twice as a coach and once with Barrow as a player. ↩︎

- Trevor Gibbons, ‘Roy Francis’ in The Glory of Their Times, ed. by Phil Melling and Tony Collins (Vertical, 2002), pp. 39-53 (p. 44-45). ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 139. ↩︎

- Perhaps exasperated by the racism he faced. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 123. ↩︎

- Somewhat surprisingly. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 154. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 155. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 161. ↩︎

- Squidge Rugby, “So Who Was Roy Francis? | A Squidge Rugby Deep Dive.” ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 165-166. ↩︎

- Unnamed Sydney Journalist in Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 169. ↩︎

- Phil Melling, ‘Billy Boston’ in The Glory of Their Times, ed. by Phil Melling and Tony Collins (Vertical, 2002), pp. 54-65 (p. 55). ↩︎

- Peter Jackson, “Billy Boston: Welsh Rugby Legend Who Never Played at the Arms Park,” BBC Sport, December 5, 2016 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/wales/38206765>. ↩︎

- “Cardiff Internationals RFC,” Cardiff Internationals RFC <https://web.archive.org/web/20241209055753/https://cardiffinternationals.rfc.wales/club-history>. ↩︎

- Jackson, “Billy Boston: Welsh Rugby Legend Who Never Played at the Arms Park.” ↩︎

- Hitt, “The Lost Welsh Rugby Heroes Who Never Got to Play Union for Wales Because They Were Black.” ↩︎

- ITV Sport, “Exiles to Icons: The Codebreakers Come Home | Careers of Billy Boston, Clive Sullivan & Gus Risman.” ↩︎

- Jackson, “Billy Boston: Welsh Rugby Legend Who Never Played at the Arms Park.” ↩︎

- BBC, “The Rugby Code Breakers.” ↩︎

- Robert Gate, Billy Boston: Rugby League Footballer (London: London League Publications Ltd, 2009), pp. 49. ↩︎

- Jackson, “Billy Boston: Welsh Rugby Legend Who Never Played at the Arms Park.” ↩︎

- Ian Golden, “Boston, Risman and Current Wales Players Honoured – Wales Rugby League,” Wales Rugby League – Official Website, April 27, 2016 <https://wrl.wales/boston-risman-and-current-wales-players-honoured>. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 67. ↩︎

- As well as several other matches throughout the first Australian leg of the tour. ↩︎

- Wikipedia contributors, “1954 Great Britain Lions Tour,” Wikipedia, December 2, 2024 <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1954_Great_Britain_Lions_tour>. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 113. ↩︎

- Collins, Roy Francis: Rugby’s Forgotten Black Leader, pp. 113. ↩︎

- Melling, ‘Billy Boston’ in Melling and Collins, The Glory of Their Times, pp. 54-65 (p. 58). ↩︎

- Gate, Billy Boston: Rugby League Footballer, pp. 145-146, 271. ↩︎

- Melling, ‘Billy Boston’ in Melling and Collins, The Glory of Their Times, pp. 54-65 (p. 58). ↩︎

- Signing the contract 18 months after ‘retiring’ with Wigan. ↩︎

- BBC, “The Rugby Code Breakers.” ↩︎

- These matches were not capped games; however, the rest of both teams would go on to receive full caps. Boston did not due to injury. ↩︎

- Golden, “Boston, Risman and Current Wales Players Honoured – Wales Rugby League.” ↩︎

- ITV Sport, “Exiles to Icons: The Codebreakers Come Home | Careers of Billy Boston, Clive Sullivan & Gus Risman.” ↩︎

- Abbie Wightwick, “The Rugby Legend Wales Didn’t Want Because of the Colour of His Skin,” Wales Online, June 10, 2025 <https://www.walesonline.co.uk/sport/rugby/rugby-news/rugby-legend-wales-didnt-want-31824679>. ↩︎

- Two British and two Kiwi rugby league players have previously been knighted, however these were for either war efforts or public service. ↩︎

- Sky Sports, “Billy Boston: First Non-White Player to Represent Great Britain on a Lions Tour Receives Rugby League’s First Knighthood.” ↩︎

- PA News Agency, “Rugby League Star Sir Billy Boston’s Knighthood ‘a Little Bit Late’, Says Son,” Border Counties Advertizer, June 10, 2025 <https://www.bordercountiesadvertizer.co.uk/news/national/25228963.rugby-league-star-sir-billy-bostons-knighthood-a-little-bit-late-says-son/>. ↩︎

- Billy Boston in Gate, Billy Boston: Rugby League Footballer, pp. 411. ↩︎

- James Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story (Worthing, Sussex: Pitch Publishing, 2017), pp. 34. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 34. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 35. ↩︎

- Bev Risman, ‘Clive Sullivan’ in Melling and Collins, The Glory of Their Times, pp. 129-139 (p. 132). ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 36. ↩︎

- Risman, ‘Clive Sullivan’ in Melling and Collins, The Glory of Their Times, pp. 129-139 (p. 131). ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 35-36. ↩︎

- Macfarlane, “Clive Sullivan: Who Was Welsh Rugby League Icon, When Did He Die – and Why Is a Google Doodle Celebrating Him?” ↩︎

- Rebecca Nelson, “Clive Sullivan,” African Stories in Hull & East Yorkshire <https://www.africansinyorkshireproject.com/clive-sullivan.html>. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 39. ↩︎

- Risman, ‘Clive Sullivan’ in Melling and Collins, The Glory of Their Times, pp. 129-139 (p. 132). ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 43. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 43-44. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 45-47. ↩︎

- Sullivan broke his shoulder and three ribs in the crash, as well as severely damaging his lung. This occurred only two months before he was due to leave the army. ↩︎

- Risman, ‘Clive Sullivan’ in Melling and Collins, The Glory of Their Times, pp. 129-139 (p. 132). ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 125-126. ↩︎

- Rosalyn Sullivan in Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 48. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 81. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 80, 95. ↩︎

- Risman, ‘Clive Sullivan’ in Melling and Collins, The Glory of Their Times, pp. 129-139 (p. 134). ↩︎

- Nelson, “Clive Sullivan.” ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 125. ↩︎

- Clive Sullivan in Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 119. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 132-133. ↩︎

- Many league players report that the barely broke even during this period. Although professional by name, travel and missed time payments barely covered the players actual expenses nor their missed wages from their day jobs. On top of that, many did not receive any payment if they were injured whilst playing which means they could go months without any form of wages. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 18. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 19. ↩︎

- Ironically, against Hull FC. ↩︎

- Via a stint at Oldham. ↩︎

- Heavy on the “coach” and light on the “player” ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 203. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 215-216. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 217. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 218. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 218. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 219. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 219. ↩︎

- BBC, “The Rugby Code Breakers.” ↩︎

- George Zielinski, “Roy Francis Monument Honours Black Rugby League Pioneer,” BBC News, October 22, 2023 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-67181749>. ↩︎

- Risman, a fellow Welsh codebreaker, was white but he was of Latvian descent and came up in Welsh rugby union when selectors excluded those of non-Welsh descent almost entirely. ↩︎

- ITV Sport, “Exiles to Icons: The Codebreakers Come Home | Careers of Billy Boston, Clive Sullivan & Gus Risman.” ↩︎

- As well as the many more not featured in this article. ↩︎

- Oddy, True Professional: The Clive Sullivan Story, pp. 219-220. ↩︎

- To highlight this, the headquarters of the National Front was in Hull. ↩︎

Leave a comment