As Canada prepares for the 2025 Rugby World Cup, they are once again faced with balancing fundraising and on-field preparation.

The Great White North may not seem like a natural fit for a flourishing rugby culture, with its often snow-covered pitches and nationwide hockey obsession. However, rugby’s cultural values of being hardworking and humble align well with Canadian culture, according to current women’s national team captain Sophie de Goede1. Men’s rugby has a long and storied history in Canada, with rugby serving as a precursor to the country’s native game of Canadian football, and it was also an early adopter of the women’s game. Despite this deep history, in the modern era, rugby in Canada has suffered from several significant hindrances, which has damaged the men’s programme and led to limited success on the international stage. In comparison, despite chronic underfunding, a lack of a cohesive domestic structure and national set-up controversies, the women’s team has risen to the current number two side in the world and a world-leading sevens programme.

Rugby has a long but complicated history in Canada. The sport was introduced by British settlers and soldiers during the mid-nineteenth century, with a game between soldiers and students taking place in Montreal in 18652. Like their southern neighbours, Canadians were quick to develop their own laws, with Canadian football soon becoming the predominant form of the game in the country. This led the sport we know today as rugby union as a ‘sport of the past’ in Ontario and Quebec by the early 1880s3. However, rugby union did continue to be played by small minorities throughout Canada, with a stronghold in British Columbia, resulting in reciprocal tours between Japan and Canada in 1930 and 19324. Whilst the Canadian national men’s team has often been considered to be a regional giant, they have not been able to continue to compete with more traditional rugby nations. With a significantly smaller budget than tier one nations, a small player pool, a lack of domestic senior rugby opportunities and legislative issues within Rugby Canada, the men’s team have struggled to attain any measure of form in recent years. Whilst the team were Rugby World Cup mainstays following the competition’s 1987 founding, they failed to qualify for the 2023 edition and lost six of their seven matches in 20245. The failure to qualify for the 2023 World Cup has also impacted the team’s ability to bounce back due to decreased funding from World Rugby.

Whilst France is arguably the birthplace of the modern women’s rugby movement, North America took the game to a new level. In the 1970s, university and club sides began popping up across North America, with those north of the border enjoying the benefits of full membership of their union and the most support from any integrated union in the world6. The first official and independent Women’s rugby club in Canada was founded in 1979 in Ottawa, Ontario7. The Ottawa Banshees remained independent from a male club until 2002 and continue to play to this day. More clubs began to pop up around Canada, leading to representative provincial sides and the Provincial Championships, the first of which was held in 1987 in Calgary8. It would be in the same year that Canada made their test match debut.

Following on from successful tours of Europe by American club sides, the first test match outside of Europe (featuring the USA and Canada) was planned for 1987, five years on from the first ever Women’s international test match between the Netherlands and France. The match took place on 14th November 1987 in Victoria, British Columbia and acted as a curtain raiser to a contentious Canada v USA men’s match. Whilst the USA Women’s team was sanctioned by USA Rugby, the team were not allowed to call themselves the Eagles nor were they allowed to wear the famous badge, as the union were still not fully supportive of women’s rugby9. In comparison, Canada had full support of their national union and wore the famous maple leaf with pride. The USA, the majority of whom had toured Europe, won the match by 22 points to 3. The initial Canadian team however set an example for all future Canucks, with the USA team noting how physical and unrelenting their opponents were.

‘The thing about Canada is that they were much tougher than we were. They have always been incredibly physical and tough. We tackle hard but at the breakdown we are not as physical on a constant basis like they are. We won the game alright, but it was an awakening to say ‘oh this is international rugby’, because nobody had ever done it and we were the first.’

Kathy Flores, 1987 USA captain and number 810.

Not only did the 1987 match cement a tradition of physical relentlessness for Canada and start one of the fiercest rivalries in Women’s rugby, but it also created a family legacy. Stephanie White captained the side from number 8, and she would go on to receive 17 caps for the Maple Leafs. White co-captained the side at the 1991 World Cup and captained the team at the 1994 World Cup, as well as captaining the first-ever Canadian sevens team in 199711. Alongside her playing career, White balanced a career in rugby administration, having sat on various governing boards at both provincial and national levels. However, despite White’s success in both of these areas, in recent years she has entered the spotlight as the mother of current Canada captain Sophie de Goede. The de Goede family name has become synonymous with Canadian rugby worldwide. Dutch-born patriarch Hans de Goede captained the Canadian Men’s fifteens and sevens sides and also had spells playing in Europe and Oceania, most famously with Cardiff RFC in the late 1970s12. As a player, Hans was so well-renowned during the 1980s that he twice featured in ‘World XV’ sides despite coming from a country known as somewhat of a rugby minnow. Hans retired from playing in 1987, after captaining Canada at the first Men’s Rugby World Cup, where he was famously caught on radio mics during a win over the much-favoured Tonga as saying ‘Come on boys, we’re making history!’13. Sophie’s older brother, Thyssen, has also represented Canada twice in XVs, both caps coming during the 2015 Pacific Nations Cup. Since retirement, Stephanie and Hans have both become members of the Rugby Canada Hall of Fame14.

A key element of White’s work within Canadian rugby has been her efforts to end the ‘pay to play’ model, which has dominated the funding structure of the national team since its inception and to also increase the funding for the programme. Pay to play has a long history within women’s rugby, and whilst financial struggles are not new to Rugby Canada, the Canadian women’s national team has been forced to pay their way and engage in fundraising efforts for far longer than any of the other top female sides. Whilst at the first Women’s World Cup in 1991, the USSR team infamously clashed with the British tax office over the team’s attempts at fundraising15, the Canadians are making headlines for their World Cup fundraising efforts in 2025, despite being favourites for the final and having their eyes on the trophy.

Scrum Queens began reporting on the financial hardships faced by the Maple Leafs back in 20101617. Rugby Canada had been forced to pull out of a World Cup warm-up tour of New Zealand due to financial hardships. Rugby Canada later received $150,000 in extra funding for the 2010 World Cup through provincial and outside donors18. This was $30,000 more than the team’s $120,000 yearly budget allocated to the team by Rugby Canada. Team members noted that an appropriate budget was important for the team’s well-being and on-pitch performance, comparing it to the nation’s success at the 2010 Winter Olympics. The Winter Olympics had shown that female rugby players could be successful athletes, as national team member Heather Moyse won gold in the two-man bobsled. Moyse had previously been the top try scorer at the 2006 World Cup and would later go on to once again top the try scoring charts at the 2010 World Cup. Whilst Moyse received financial backing from Sport Canada for her participation in the Winter Olympics, Moyse would’ve paid approximately $3000 per tournament for the privilege of representing her country in her preferred sport of Rugby. Scrum Queens reported that an athlete who took part in a full four-year World Cup cycle between 2006 and 2010 would’ve spent approximately $36,000; however, this figure does not include any financial losses the players would’ve suffered due to taking extended breaks from work to attend competitions. Canada would ultimately finish sixth at the 2010 World Cup, their joint lowest finish at the competition.

‘It’s amazing to see how important people think it is that we need to focus on the game itself and not be stressed financially. I think Canada’s success in the Olympics proved that financial support for athletes can make them perform better and achieve their best. We are honored and lucky to have such a great rugby community in our country.’

Brooke Hilditch, Canadian World Cup 2010 Team Member19

The following year, a group of players, including Brooke Hilditch, opted to boycott the 2011 Nations Cup20 in protest. To compete in the competition, Rugby Canada required the players to pay $2900 to play in an international competition which was taking place in Canada. In comparison, the Canadian Men’s team received approximately $1.7 million per year in World Rugby21 funding in this period and also had all of their World Cup costs covered by the governing body (roughly $400 000). Despite the 2010 press coverage, 2011 boycott and the team’s second-place finish at the 2014 World Cup, the team were still paying to represent their nation in 2016. Perhaps due to the bad press associated with the 2011 boycott, the costs of each tour had been reduced to approximately $150022 by 2016, however, not only had Canada’s rivals moved away from that model but Rugby Canada had also stopped pay to play for the men’s team decades previously. Ahead of the 2017 World Cup, the Monty Heald Fund was set up to centralise fundraising efforts, and Rugby Canada noted that the pay-to-play model needed to be eliminated as soon as possible. The fund was headed up by Stephanie White, and as a result, no player used their own money to take part in the 2017 World Cup2324.

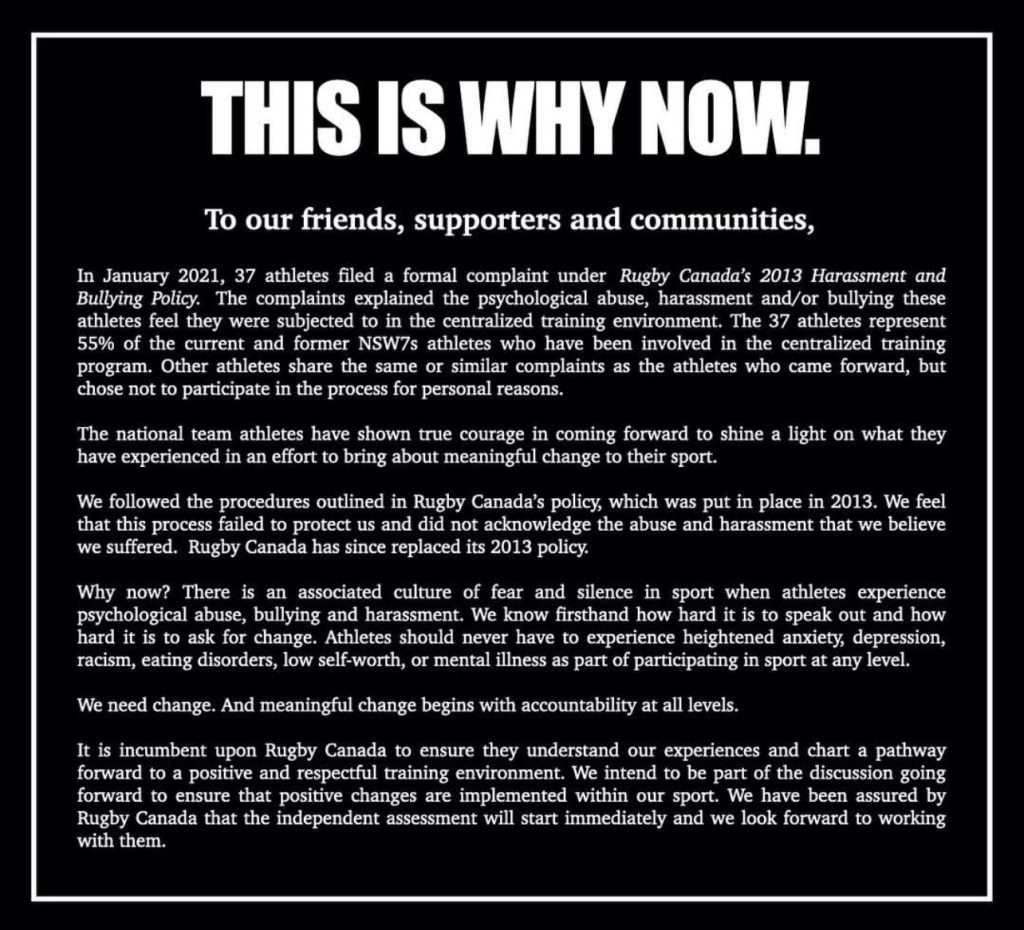

The 2010s brought an additional means of funding for Canadian rugby, but it also came with more responsibility for the players and additional controversy. Rugby sevens became an Olympic sport in 2016, which resulted in the women’s sevens programme receiving $750,000 from the “Own the Podium” programme25 and full-time contracts for selected players as a result of the newly founded women’s sevens circuit. The seven’s team won a bronze medal at the 2016 games but dropped to ninth place at the 2020 games26. During the lead-up to the Tokyo games, the team submitted a complaint to Rugby Canada, citing bullying and harassment. This resulted in head coach John Tait stepping down just months before the start of the games27. Although Rugby Canada found through an independent investigation that whilst the players’ experiences did match those within the complaint, they did not meet the threshold for the governing body’s policy definition of harassment and bullying. The complaint had been signed by 37 athletes, 21 of whom were in the then-current playing pool and in total represented 55% of those who had attended training camps in British Columbia.

“We know firsthand how hard it is to speak out and how hard it is to ask for change. Athletes should never have to experience heightened anxiety, depression, racism, eating disorders, low self-worth or mental illness as part of participating in sport at any level.”

Canadian Women’s National Sevens Team statement, 202128

Canada has utilised their small playing pool to the extreme, with the majority of sevens players also playing for the national fifteens squad as well. This means that a significant portion of the squad that finished fourth at the 202129 World Cup had been subjected to bullying and harassment under Rugby Canada.

The post-pandemic era has been one of great success for Canadian women’s rugby. The team has won two PAC4 tournaments and recorded their first-ever win over New Zealand, whilst the sevens team won silver at the 2024 Olympics. Despite this, the team still faces significant issues over funding, which has resulted in players spending their time fundraising whilst attempting to prepare for the Rugby World Cup. Following on from their recent success, Rugby Canada launched “Mission Win The Rugby World Cup” in March 202530 with the aim to raise $1 million to supplement the team’s $2.6 million budget. Whilst sponsorships and donations are key for a nation with a low domestic profile, the fundraising has highlighted how the Canadian women’s team are disadvantaged in comparison to their competitors and risk falling behind like the Canadian men’s team did upon professionalisation in the men’s game.

As of June 2025, the Canadian XVs players have individual player agreements with Rugby Canada. The agreements cover travel and accommodation, as well as compensating players for their time when they are in camp, as well as match fees31. Unlike the central contracts offered to players in Wales or England, if Canadian players are not called up into camp due to form or injury, they are not paid. Whilst a handful of players are contracted by the Canadian Sevens programme and spend the majority of their time on the SVNS circuit, the rest of the squad balance playing elite rugby with a career. The majority of the squad play in the PWR in England, a semi-professional league with a hard salary cap. Smaller numbers of players play in the Elite 1 in France (predominantly Quebecois players), and other individuals have found success in leagues in the USA, Australia and New Zealand. Whilst there are individuals across many of the top squads who are not full-time professional players (such as Neve Jones of Ireland and Emma Sing from England), Canada’s continued amateur status is at odds with the professionalisation of the game.

As the team looks forward towards the 2025 World Cup in England, they are continuing their fundraising efforts alongside their on-field preparation. Whilst the squad may not be officially “paying to play” anymore, they are using their time and energy to aid in financing their campaign. For example, hooker Holly Phillips has been active on social media promoting the fundraising efforts and has also conducted interviews on the subject3233. Whilst Rugby Canada has calculated that $3.6 million will cover the costs of the World Cup, the Canadian budget is minuscule in comparison to the budgets of England ($26.5 million), New Zealand ($10 million) and Scotland ($6.5 million)3435. Whilst the Canadian men’s team has also faced significant financial issues and players are also required to ply their trades outside of Canada, they can play professionally without balancing an outside career and also do not face the significant pressures that the women’s team faces as a successful flagship programme.

Moving beyond the upcoming World Cup, it feels that the programme is at a crossroads. Whilst Rugby Canada has relied heavily on sevens and outside domestic competitions for their players to get game time, both of these avenues are facing significant changes. The 2025-26 SVNS season will be undergoing serious changes with fewer tournaments36, with many nations cutting their full-time programmes in response37. Additionally, as more national teams move towards central contracts, more players are now playing and training as full-time professionals, putting Canadians at a disadvantage. Overseas club competitions are also changing: the relatively new Celtic Challenge is providing Welsh, Scottish and Irish players a chance to play domestically as is the WER in the USA; the PWR has enacted rules surrounding a minimum number of English qualified players38 and the Elite 1 in France contracted from twelve to ten teams before the 2024/25 season39. These changes signal that Canada is falling behind in terms of domestic development and is leaving players at risk of falling behind in comparison to their competitors. Whilst the Canadian players themselves are among the best in the world and the team is capable of dominating the world scene on raw skill, talent and pure determination, as Women’s rugby continues to professionalise in other countries, Rugby Canada risks repeating the mistakes they undertook with their men’s programme.

It is imperative that Rugby Canada invest in their women’s programme, providing their players with a livelihood and the opportunity to play in high-level domestic competition in order to grow the sport and to develop their team further. Whilst this will require significant outside investment, the efforts to court said investment should not fall on the shoulders of active players alone. It is also incredibly important that the investment in the women’s game trickles down to age grade and grassroots rugby, so that all girls have a chance to play and that those who want a future in the sport should be able to do so without financial barriers. Whilst almost three decades have passed since former Alberta head coach John Arthur O’Hanley wrote his dissertation on the women’s game in Canada, many of his findings are still relevant. Whilst he spoke of Canadian women having an equal opportunity to Canadian men in 1998, a 2025 evaluation of the state of Canadian women’s rugby would show that Canadian women deserve equal opportunities and access as their international competitors to encourage the continued success of the programme.

‘A determined effort should be made to ensure that women in rugby have an equal opportunity to participate and play. They must have access to the same coaching, facilities, officiating and equipment as their male counter-parts. This is the responsibility not only of the rugby unions, but of each individual club in Canada. There can be no second class citizens in rugby. The women will not tolerate it and the sport requires it.’

John Arthur O’Hanley, 199840

I hope you have enjoyed the second edition of The Rugby History Project. References and notations can be found below. If you would like more information about Canada’s “Mission Win The Rugby World Cup”, please click here, and if you would like to donate directly, please click here.

-Hattie

Thanks for reading The Rugby History Project! Subscribe for free to receive new posts, or consider upgrading to Historian Tier to support the project!

- de Goede, in Sheena Goodyear, “Canada Has One of the Best Women’s Rugby Teams in the World. Why They’re Asking for Your Money,” CBC, March 12, 2025 https://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/rugby-womens-world-cup-fundraiser-1.7480474. ↩︎

- Huw Richards, A Game for Hooligans, 2nd edn (Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2007), pp. 35-36. ↩︎

- Richards, A Game for Hooligans, pp.53. ↩︎

- Richards, A Game for Hooligans, pp.143. ↩︎

- Additional information regarding the Canadian National Men’s Team and their recent issues with results can be found here: HG Rugby, “Canada Rugby: Tale of Two Sexes (Mini-Documentary),” YouTube, September 28, 2024 https://youtu.be/aOoIqk1I5QM?si=uVuiWjVU_OdznSUA. ↩︎

- Ali Donnelly, Scrum Queens (Chichester, West Sussex: Pitch Publishing, 2020), pp. 37. ↩︎

- “Banshees History | Ottawa Beavers-Banshees RFC,” Ottawa Beavers-Bansh https://www.obbrfc.com/banshees-history. ↩︎

- Donnelly, Scrum Queens, pp. 40. ↩︎

- Donnelly, Scrum Queens, pp. 59. ↩︎

- Flores, in Donnelly, Scrum Queens, pp. 59. ↩︎

- The Canadian Ruck, “Hans & Stephanie de Goede – Season 2, Episode 14,” YouTube, March 13, 2021https://youtu.be/ZQd-_Q-_Lvs ↩︎

- “Player – Hans de Goede,” Cardiff RFC http://cardiffrfc.com/player?id=100859&authtoken=N0MwRjlEMjYtMTU5Ni00RjdCLTk4Q0YtMzAxQUIyQTdEQkVG&teamid=MTAzOTY5. ↩︎

- Richards, A Game for Hooligans, pp. 220. ↩︎

- Neil M Davidson, “Rugby Canada Hall of Fame a Family Affair for de Goede,” TSN, January 22, 2019 https://www.tsn.ca/rugby-canada-hall-of-fame-a-family-affair-for-hard-nosed-forward-hans-de-goede-1.1245381. ↩︎

- Martyn Thomas, “Chapter 13: Resourceful Russians,” in World in Their Hands (Edinburgh: Polaris, 2020), pp. 189–202. ↩︎

- “Canada Plea for Financial Backing,” Scrum Queens, March 2010 <https://web.archive.org/web/20230206052644/https://www.scrumqueens.com/news/canada-plea-financial-backing>. ↩︎

- “Canada Handed Huge Boost,” Scrum Queens, March 2010 <https://web.archive.org/web/20231209053002/https://www.scrumqueens.com/news/canada-handed-huge-boost>. ↩︎

- All figures in Canadian Dollars. ↩︎

- Hilditch, in “Canada Handed Huge Boost.” ↩︎

- Mary Ormsby, “Female Rugby Stars Won’t Pay to Play,” Thestar.Com, July 28, 2011 <https://web.archive.org/web/20181203055516/https://www.thestar.com/sports/2011/07/28/female_rugby_stars_wont_pay_to_play.html>. ↩︎

- Then known as the IRB. ↩︎

- “End to Pay-to-Play for Canada’s Women?,” Scrum Queens, March 10, 2016 <https://web.archive.org/web/20160812194110/http://www.scrumqueens.com/news/end-pay-play-canadas-women>. ↩︎

- “MONTY HEALD NATIONAL WOMEN’S FUND – Canadian Rugby Foundation,” Canadian Rugby Foundation – Investing in the Future of Canadian Rugby, December 4, 2017 https://canadianrugbyfoundation.ca/index.php/monty-heald-national-womens-fund-2/. ↩︎

- Pay-to-play continues for age-grade rugby within Canada, with costs in 2024 ranging from $500 to $1500 per tournament. As the players pay through their provincial unions, the costs vary from province to province. More details can be found here: Alice Soper, “THE PROFESSIONAL ERA: PART 2 – ScrumQueens,” Scrum Queens (Scrum Queens, September 23, 2024) https://scrumqueens.com/features/the-professional-era-part-2. ↩︎

- Ormsby, “Female Rugby Stars Won’t Pay to Play.” ↩︎

- The 2020 Tokyo games were delayed to 2021 due to the Covid 19 pandemic. ↩︎

- Neil Davidson, “Rugby 7s Women Say They Were Let down by Rugby Canada’s Bullying/Harassment Policy,” CBC, April 28, 2021 https://www.cbc.ca/sports/rugby/rugby-sevens-women-let-down-rugby-canada-bullying-harrassment-policy-1.6005901. ↩︎

- Davidson, “Rugby 7s Women Say They Were Let down by Rugby Canada’s Bullying/Harassment Policy.” ↩︎

- The 2021 World Cup took place in 2022 due to the Covid 19 pandemic. ↩︎

- “Rugby Canada Launches Mission: Win Rugby World Cup Fundraising Campaign,” Rugby Canada, July 3, 2025 https://rugby.ca/en/news/2025/03/rugby-canada-launches-mission-win-rugby-world-cup-fundraising-campaign. ↩︎

- Alice Soper, “The Professional Era: Part 1 – ScrumQueens,” Scrum Queens, August 20, 2024 https://scrumqueens.com/features/the-professional-era-part-1. ↩︎

- The Women’s Rugby Show, “THE SACRIFICES OF A RUGBY PLAYER I Exploring Canada’s Journey to the RWC,” YouTube, June 27, 2025 https://youtu.be/-chvD9llNhA ↩︎

- Holly Phillips, “Never Did Struggle for a Word Count 🤭 Poor Bloke Just Wanted a Simple answer… Let’s Face It Women’s Rugby Needs to Win in 2025 … Can’t Say It Enough,” X (Formerly Twitter), June 25, 2025 https://x.com/Hollygphillips2/status/1937187522058289329. ↩︎

- @RugbyStruggles, “A Non-Funny Struggle/PSA: Canada Women Operate on Approximately $2.5 Million Canadian a Year. In Comparison, England Spend about $26.5m, NZ $10m and Scotland $6.5m. Canada Women Need Investment to Not Only Reward Their Performance and Hard Work, but to Build for the Future.,” X (Formerly Twitter), June 23, 2025 https://x.com/rugbystruggles/status/1937196306310541790. ↩︎

- All figures in Canadian Dollars, figures reported to @RugbyStruggles by a reputable source. ↩︎

- World Rugby, “World Rugby Unveils Evolved SVNS Model ? HSBC SVNS,” May 1, 2025 https://www.svns.com/en/news/999470/world-rugby-unveils-evolved-svns-model. ↩︎

- David Barnes, “World Rugby, the HSBC SVNS Series and Why It Isn’t Working like It Could,” The Offside Line (The Offside Line, June 2, 2025) https://www.theoffsideline.com/world-rugby-the-hsbc-svns-series-and-why-it-isnt-working-like-it-could/. ↩︎

- “Club Statement: RFU Points Deduction,” Leicester Tigers, February 9, 2024 https://www.leicestertigers.com/news/clubnews-tigerswomens-240209. ↩︎

- Jonah Lomu, “Féminines : les poules Elite 1, 2 et fédérales officialisées – Rugby Amateur,” RugbyAmateur.fr (RugbyAmateur.Fr, July 4, 2024) https://rugbyamateur.fr/feminines-poules-elite-1-2-federales-officialisees/#google_vignette. ↩︎

- John Arthur O’Hanley, “Women in Non-Traditional Sport : The Rise and Popularity of Women’s Rugby in Canada” (unpublished MA Thesis, Queen’s University at Kingston, 1998) http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA43177865, pp. 77. ↩︎

Leave a comment