Sione Tuipulotu’s inclusion within the 2025 British & Irish Lions Tour to Australia has ruffled feathers. This article looks at Alfred Clunies-Ross, Scotland’s first diaspora player.

The inclusion of current Scotland Men’s Captain Sione Tuipulotu in the 2025 British & Irish Lions squad has created an incredible amount of vitriol on social media. In recent years, Tuipulotu has faced increasing amounts of abuse for his lineage and his decision to represent Scotland over his birthplace of Australia. However, Tuipulotu’s inclusion in Scotland and British & Irish Lions squads is just the latest example of the role of diaspora in Scottish rugby, which dates back to the first-ever international test match.

Tuipulotu’s decision to represent Scotland, and therefore his eligibility to represent the Lions, is made possible through World Rugby’s ancestry qualification grounds, which allows players to play for the birth nation of their parents and grandparents. This qualification process was also used by fellow 2025 Australian-born Lions tourist Finley Bealham, who has an Irish-born grandmother. In Tuipulotu’s case, his maternal grandmother, Jacqueline, was born in Greenock, a small town 25 miles east of Glasgow. Jacqueline later emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, where she married an Italian-born man and gave birth to Tuipulotu’s mother, Angelina. Angelina would go on to have a relationship with Fohe Tuipulotu, who is Tongan, and have five children, including professional rugby players Sione, Mosese and Ottavio1. Whilst Bealham (who is visibly White) is rarely on the receiving end of nativist abuse, Sione Tuipulotu is frequently used as an “example” of the supposed “issues” regarding World Rugby’s qualification processes, with vocal opponents calling into question his Scottishness due to his mixed heritage and Australian birth. Tuipulotu is far from the first diaspora player to play for Scotland. In fact, in the first-ever international rugby match in 1871, the Scottish team included diaspora player Alfred Clunies-Ross at fullback.

Alfred Clunies-Ross was born in the Cocos Islands, a small archipelago roughly 600 miles east off of the coast of Australia, in 1851. The Clunies-Ross family were a family of Scottish origin who had settled in the islands in 1827, taking control from English colonialist Alexander Hare and appropriating Hare’s group of Indonesian and Malay slaves. Alfred’s grandfather, John Clunies-Ross, had been born in the Shetland Islands and travelled frequently as a merchant and ships captain. During this period, he travelled to the Cocos Islands for the first time. John Clunies-Ross would later become known as the “King of the Cocos”2, and by 1837, the Clunies-Rosses agreed to pay the island’s slaves 8 pence a day for manual labour upon a command from the captain of HMS Pelorus3, displaying the acceptance of the island as a part of the British Empire. Alfred’s father, John George, had been only four in 1827 when his father John moved his family across the globe, and eventually married a woman known as S’pia Dupong, who was either Indonesian or Malay4. Alfred was raised in the small community on the Cocos Islands before being sent to Scotland for his education, where he studied at Madras College and then St. Andrew’s. Whilst in Scotland, Clunies-Ross was known as a keen sportsman and her played alongside James G. Robertson, a Gambian-born player of mixed Scottish and Gambian descent5.

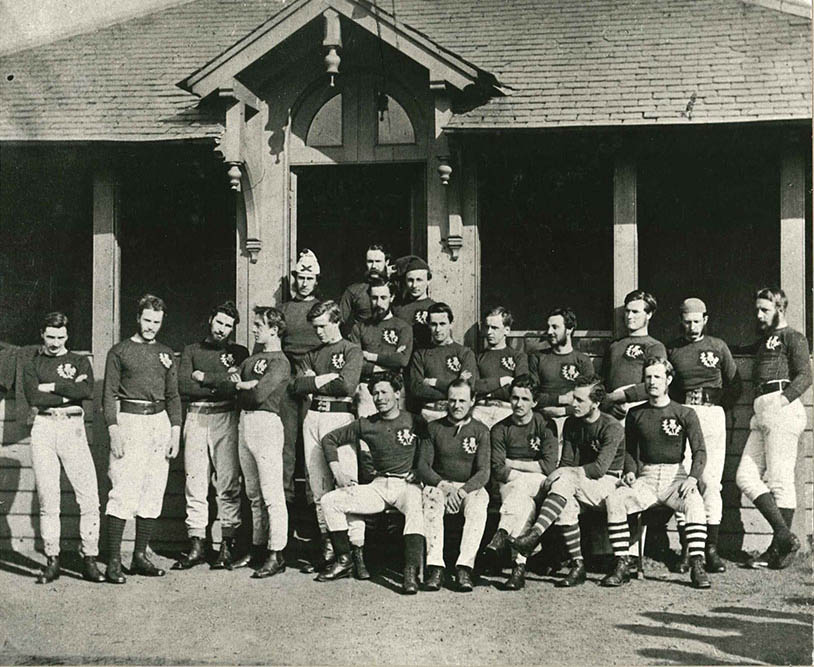

As a member of the University of St Andrew’s RFC, Clunies-Ross impressed and subsequently attended trials to represent Scotland in 1871 for the first-ever international rugby match. The laws used for this match differed significantly from what we know today, with twenty players taking the pitch for each team6. Clunies-Ross was one of the three fullbacks who started for Scotland7; presumably, the word winger had not entered rugby terminology yet. During the match, Clunies-Ross attempted to score a drop goal, but unfortunately, it fell short8. Ultimately, Scotland would go on to win the match 1-0 under controversial circumstances due to the differences in the legal status of a knock-on910.

Clunies-Ross’s inclusion in the Scotland squad, despite not being born in Scotland, would be permissible in the modern era due to his father’s Scottish birth. However, during the time of the Empire, the concept of nationality was significantly different to our modern thoughts. The popularisation of a British identity, rather than unique Scottish, English or Irish identities11, can be linked to the Victorian period and the expansion of the British Empire. However, not only were those from the British and Irish Isles considered to be British during this period, but those from the wider Empire would also be considered British. Up until 1962, every person born within the realm of the Empire was considered British by law and held British Citizenship. Children born outside of the British Isles to parents from one of the Home Nations were also often considered to hold their parents’ nationality and ethnicity (such as Scottish) rather than a distinct colonial nationality (such as Australian or Canadian). It was also incredibly common for colonial families of a certain class to send their children back to the British Isles to attend school, as was the case with the Clunies-Ross family. Whilst there are no reported accounts written by Alfred Clunies-Ross regarding his time in Scotland, his background is not mentioned in contemporary sources, which would indicate that it was not seen as an issue to the public. Whilst Clunies-Ross probably faced discrimination due to his mixed ethnicity and appearance, he was considered Scottish due to his father and British due to his birth within the Empire, which allowed him to represent Scotland.

Clunies-Ross would not feature again for Scotland, but he did continue his rugby career first at Edinburgh Wanderers and later at St. George’s Hospital RFC and Wasps in London. He later returned to the Cocos Islands, where he practised as a doctor, despite not finishing his medical degree, and married his cousin Ellen in 188612. His elder brother George would become the third of the Clunies-Rosses to be known as the King of the Cocos, a title which would continue to be used by the family until 1978. After living an adventurous life in both Britain and Asia, Alfred Clunies-Ross passed away in 1903 in the Cocos Islands after a long illness13.

Over 150 years separate Alfred Clunies-Ross and Sione Tuipulotu, but it is incredibly easy to make a connection between two mixed-race diaspora players who have represented Scotland. Whilst there are no known personal accounts of Clunies-Ross’ time in Scotland, it seems that contemporary media sources were not phased by his mixed ethnicity. In comparison, Tuipulotu’s Tongan heritage and Australian birth are frequently mentioned in the media and brought up divisively on social media, with many accounts using his appearance as justification to deem him not Scottish. Given the history of including diaspora players in Home Nations squads, and the significantly different attitudes towards white diaspora players in the current era (such as Finley Bealham, Kyle Steyn or Mack Hansen), there is an obvious argument to be made that the backlash against the inclusion of Sione Tuipulotu in Scotland and Lions squads can be linked to the rising levels of racism and nativism. Just a month before Tuipulotu made his debut for the British & Irish Lions, British Conservative MP, and current Shadow Lord Chancellor, Robert Jenrick spoke of a “declining native White British” population as a matter of “concern” to him14. This speech followed on from the now-infamous usage of the phrase “nation of strangers” by British Labour Prime Minister Kier Starmer, harking back to Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech. This concerning language has already been spouted by the far-right Reform party on many occasions, but the usage of the language by mainstream political parties speaks volumes. It illustrates that these views have become more normalised, with people of colour and members of the diaspora, such as Sione Tuipulotu, facing the brunt of the previously unthinkable language and abuse.

I hope you have enjoyed the first edition of The Rugby History Project. References and notations can be found below!

-Hattie

Thanks for reading The Rugby History Project! Subscribe for free to receive new posts, or consider upgrading to Historian Tier to support the project!

- Jamie Lyall, “Mosese Tuipulotu: ‘I’m Not Just Sione’s Little Brother – I’ll Prove I Can Play,’” Rugbypass, May 21, 2024 <https://www.rugbypass.com/plus/mosese-tuipulotu-im-not-just-siones-little-brother-ill-prove-i-can-play/>. ↩︎

- The Newsroom, “The Shetland Sea Captain Who Became ‘King of the Cocos,’” The Scotsman, March 17, 2017 <https://www.scotsman.com/whats-on/arts-and-entertainment/the-shetland-sea-captain-who-became-king-of-the-cocos-602285>. ↩︎

- The Newsroom, “The Shetland Sea Captain Who Became ‘King of the Cocos.’” ↩︎

- Sources differ regarding Dupong’s origin; it is probable that she was Indonesian and that the Malay connection is confusion surrounding the name of the Cocos Islands Asian population, who are known as Cocos Malay. ↩︎

- Andy Mitchell, “James G Robertson – the First Black Rugby Player?,” Scottish Sport History, October 27, 2018 <https://www.scottishsporthistory.com/sports-history-news-and-blog/archives/10-2018>. ↩︎

- Alex Gordon, “The First International Rugby Match,” BBC Sport Scotland <https://www.bbc.co.uk/scotland/sportscotland/asportingnation/article/0007/print.shtml> [accessed June 22, 2025]. ↩︎

- “1871 Scotland versus England Rugby Union Match,” Wikipedia, March 23, 2025 <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1871_Scotland_versus_England_rugby_union_match>. ↩︎

- William Coupar, “Match Report – The Great Game – 27 March 1871 — Edinburgh Accies,” Edinburgh Accies, April 21, 2021 <https://www.edinburghaccies.com/news/match-report-the-great-game-27-march-1871>. ↩︎

- A ball travelling forwards (or dropped) out of the hands was not legal under English rugby laws at the time, however, it was permissible in Scotland. Due to the agreed laws the game was being played under, the final Scottish try (which led to a successful conversion) was allowed to stand despite William Cross reportedly dropping or passing the ball forwards. ↩︎

- Coupar, “Match Report – The Great Game – 27 March 1871 — Edinburgh Accies.” ↩︎

- Whilst a strong Welsh cultural identity existed within Wales, Wales itself was often considered to be a part of England and was governed as such with a shared legal system. In comparison, Scotland and Ireland (which remained in its entirety, a part of the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until 1921 following decades of campaigning and finally the Irish Revolution) retained a much stronger cultural identity and, in the case of Scotland, a separate legal system. ↩︎

- Wasps Legends Charitable Foundation, “Alfred Clunies-Ross (1851 – 1903),” Wasps Legends <https://waspslegends.co.uk/legends/alfred-clunies-ross-(1851-1903)> [accessed June 22, 2025]. ↩︎

- Wasps Legends Charitable Foundation, “Alfred Clunies-Ross (1851 – 1903).” ↩︎

- Stephen Bush, “The New Alarming Tory Language on Britishness,” Financial Times (The Financial Times, June 20, 2025) <https://www.ft.com/content/86f45cf7-2f25-4a8b-8d9b-c2326fa28e02>. ↩︎

Leave a comment